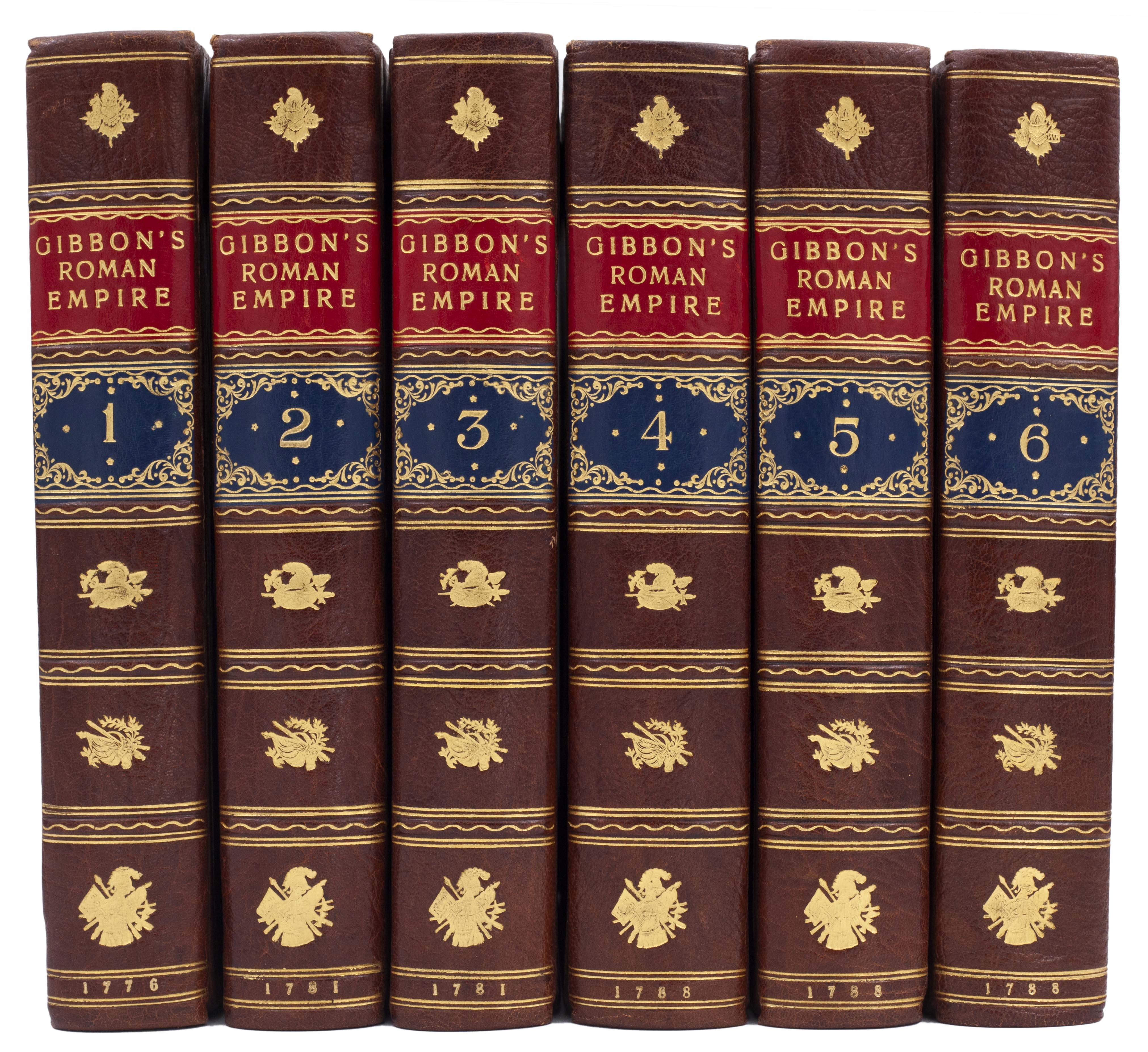

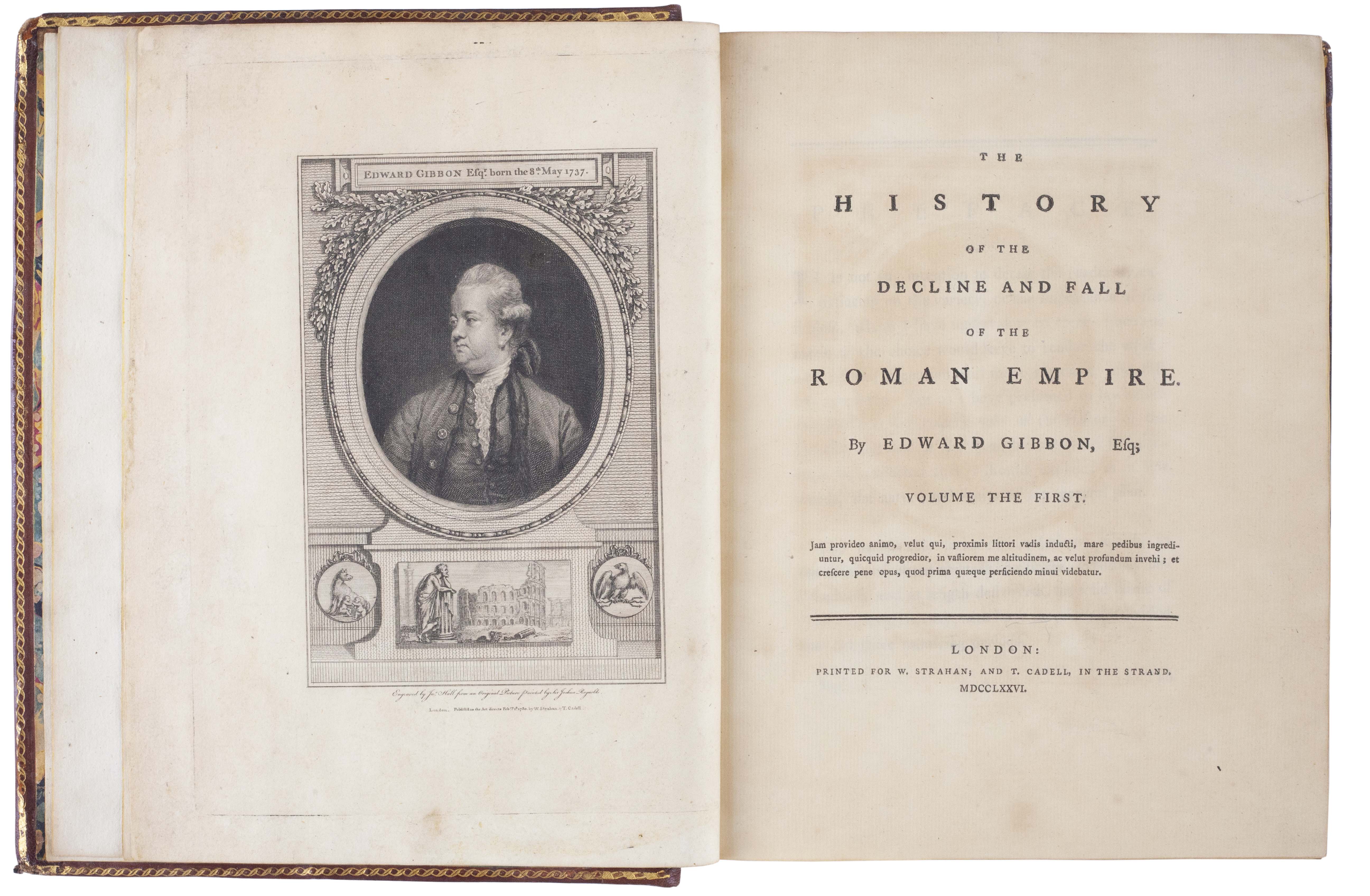

GIBBON, Edward.

The history of the decline and fall of the Roman empire.

London, printed for W. Strahan & T. Cadell, 1776–88.

Six volumes, 4to (280 x 220 mm), pp. [iii]–viii, [iv], 586, [2], lxxxviii, [1, errata]; [iii–xii], 640, [1, errata]; [iii–xi], 640, [1, errata]; [ii], viii, [viii], 620; [iii–xii], 684; [iii–xiii], 646, [52]; with a frontispiece-portrait and three folding maps; without the half-titles, vol. II without the Table of Contents of vol. I (as often); some occasional light spotting or browning as usual, some marginal staining in gathering Q of vol. II, but a very good copy in contemporary diced russia, modern reback in brown morocco, spines gilt and with contrasting red and blue calf lettering-pieces; slightly rubbed, corners and edges bumped and with consequent small losses.

First editions of all six volumes of Gibbon’s ‘masterpiece of historical penetration and literary style’ (PMM). The first volume here is of the second variant (of two), with the errata corrected as far as p. 183 and X4 and a4 so signed.

With the completion of the Decline and Fall ‘six volumes of historical narrative had lent their weight to the conviction that the threat of universal monarchy in Europe had disappeared with the fall of the Roman empire . . . . Not only was Europe now a “great republic” composed of a number of kingdoms and commonwealths, but there was no known barbarian threat; and if any should arise, America would preserve the civilization of Europe, while the simple arts of agriculture would gradually tame the new savages. From the heights of such confidence, one can perhaps understand why Gibbon should have taken the loss of the British empire in America so calmly . . . . It was far more important that the dreadful prospect of universal monarchy, for which the Roman empire had for so long been the standard-bearer, could now be exposed and discounted, enabling humanity at last to turn its back on Rome. Unfortunately, of course, it was not to be so simple. As Gibbon lived long enough to suspect, the great republic of modern Europe was not secure against a recurrence of extensive despotic empires. Just ten years after Gibbon’s death, Napoleon was crowned emperor of the French, and effectively of Europe; within a hundred and fifty years Hitler had proclaimed the thousand-year Reich. Yet if these episodes challenge Gibbon’s confidence in the end of empire in Europe, it should also be recalled that Europe would twice be saved from the east, if not by barbarians, then at least . . . by Slavs, and on the second occasion from the west as well, by Americans’ (Robertson, Gibbon’s Roman empire as a universal monarchy: the Decline and fall and the imperial idea in early modern Europe, pp. 269–70).

‘When Gibbon in his concluding pages remarks “I have described the triumph of barbarism and religion”, he may be conceding that what set out as a history of the end of the Roman empire has become a great deal more than that. The Gothic, Lombard, Frankish and Saxon barbarians replaced the western empire with systems in whose barbarism may be found the seeds of European liberty . . . . [Under] the head of religion, we face as Gibbon did the knowledge that the replacement of empire by church as the governing principle of European civilisation is a far greater matter than the secondary question of how far Christianity was a cause of the Decline and Fall. It was already a historiographic commonplace that the end of empire led to the rise of the papacy; Gibbon explored it in depth, but recognised that this theme, however great, was limited to the Latin west and that the challenge of councils, bishops and patriarchs to imperial authority . . . led to the world-altering displacement of Greek and Syrian culture by Arabic and Islamic’ (Pocock, Barbarism and Religion I, pp. 2–3).

For Gibbon’s revisions to the first volume after its original publication in 1776 and the composition of the subsequent volumes (the second and third of which did not appear until 1781) in relation to his critics and the reception of his work, see Womersley, Gibbon and the ‘Watchmen of the Holy City’, pp. 11–172.

Norton 20, 23, 29; PMM 222; Rothschild 942.