PIONEERS OF PUBLIC HEALTH

SIMON, John, Sir.

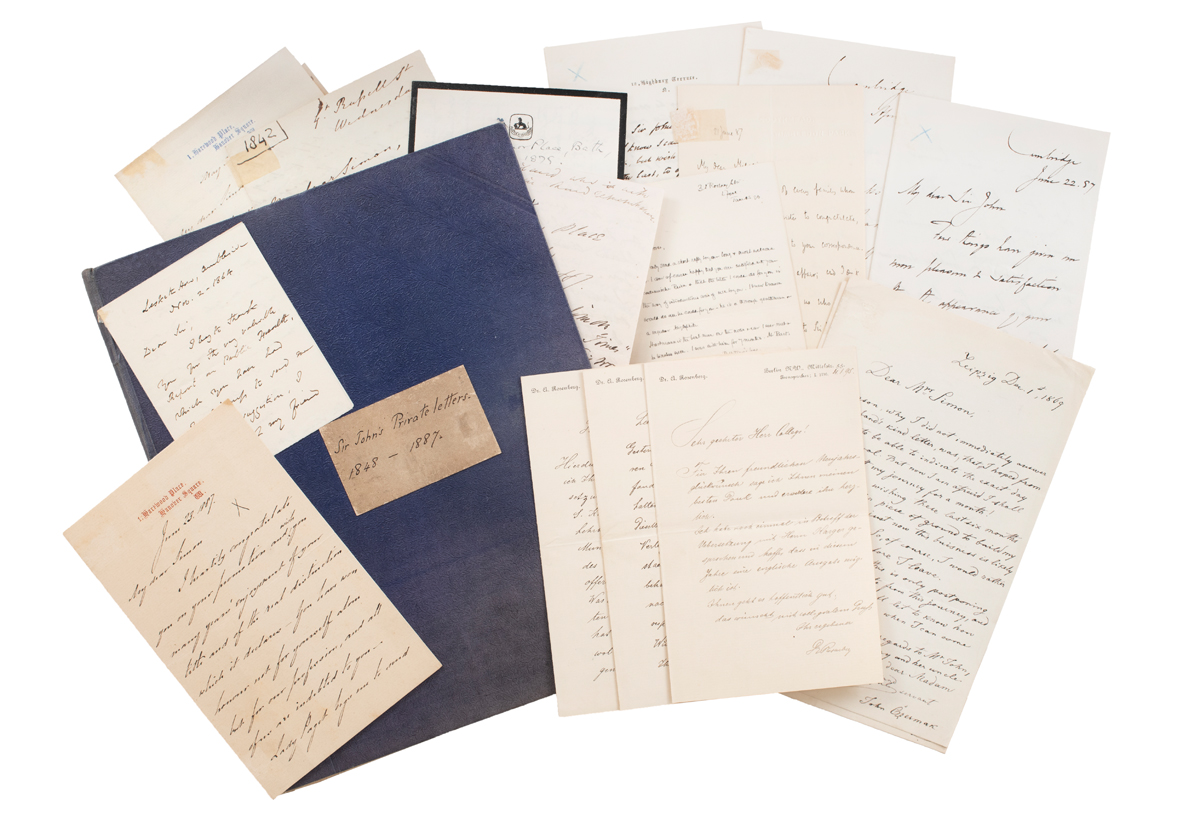

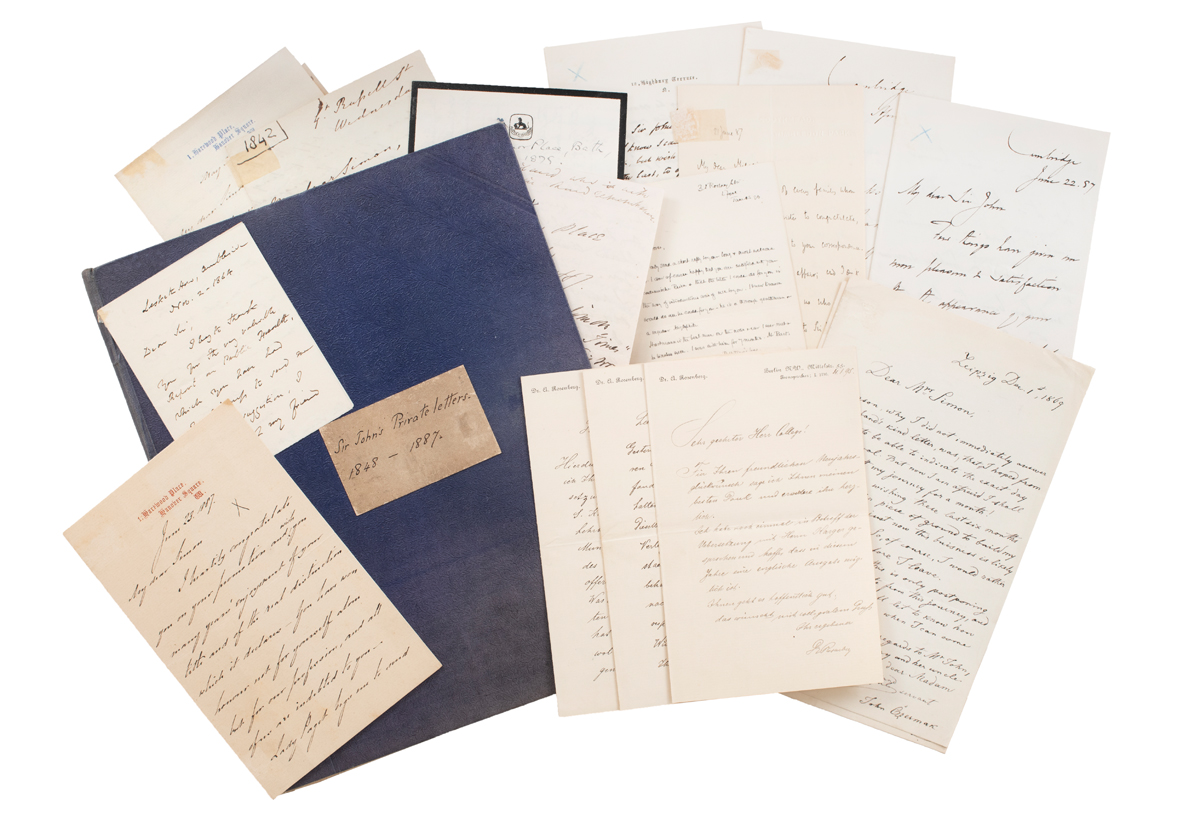

A volume of autograph letters received by Sir John Simon from medical friends and acquaintances.

Circa 1848-1887.

Large 4to, blue patterned cloth, card manuscript label to upper board; hinges cracked and binding loose; contains c. 60 autograph letters (mostly in English, some in French or in German) and a couple of additional notes and cuttings, many secured with tape, others loosely inserted; tape browned and coming away in places; letters in good condition.

Added to your basket:

A volume of autograph letters received by Sir John Simon from medical friends and acquaintances.

An interesting collection of letters to Sir John Simon and Lady Simon, from many of the leading physicians and surgeons of the Victorian era. Sir John Simon (1816–1904) was a renowned surgeon, President of the Royal College of Surgeons, and an efficient and dynamic reformer of public health in the City of London, and later more widely in England.

Simon began his career as an apprentice to Joseph Henry Green, surgeon at St Thomas’s Hospital, in 1833, and soon progressed to senior assistant surgeon at King’s College Hospital and, later, full surgeon at St Thomas’s, as well as holding a lectureship in anatomical pathology. His real break came in 1848 when he was elected the first medical health officer of the City of London sewers commission. Despite having been chosen as an ‘uncontroversial’ candidate, Simon quickly dedicated himself to highlighting the problems with public health in the City and promoting reforms in housing, sewerage, burial practices, butchering, and other areas, as detailed in his annual ‘Reports’ which were issued by The Times and later published as a collected volume. He went on to hold the post of Chief Medical Officer to the Board of Health and played a key part in investigating the cholera epidemics of the mid-nineteenth century, establishing more certainly the link first suggested by John Snow, between cholera outbreaks and contaminated water. As a pathologist, Simon was particularly interested in the transmission of diseases such as cholera, typhoid fever and diphtheria, and although he was unable to find the exact means of transmission using the tools and methods available at the time, his continued research and publicity raised awareness of the problems and encouraged reform of the overcrowded and insanitary conditions which were contributing to the outbreaks. Following his retirement from his role in public health in 1876, Simon held the post of President of the Royal College of Surgeons in 1878 and was a member of the General Medical Council. In 1887 he was created KCB and, following the publication of his English sanitary institutions reviewed in their course of development and in some of their social and political relations in 1890, he received the Harben Medal of the Royal Institute of Public Health in 1896 and the Royal Society Buchanan Medal in 1897. Simon was well-connected and well-liked in scientific, artistic, and literary circles, counting Ruskin as a close friend, and corresponding with physicians, philosophers and writers from France and Germany as well as the UK.

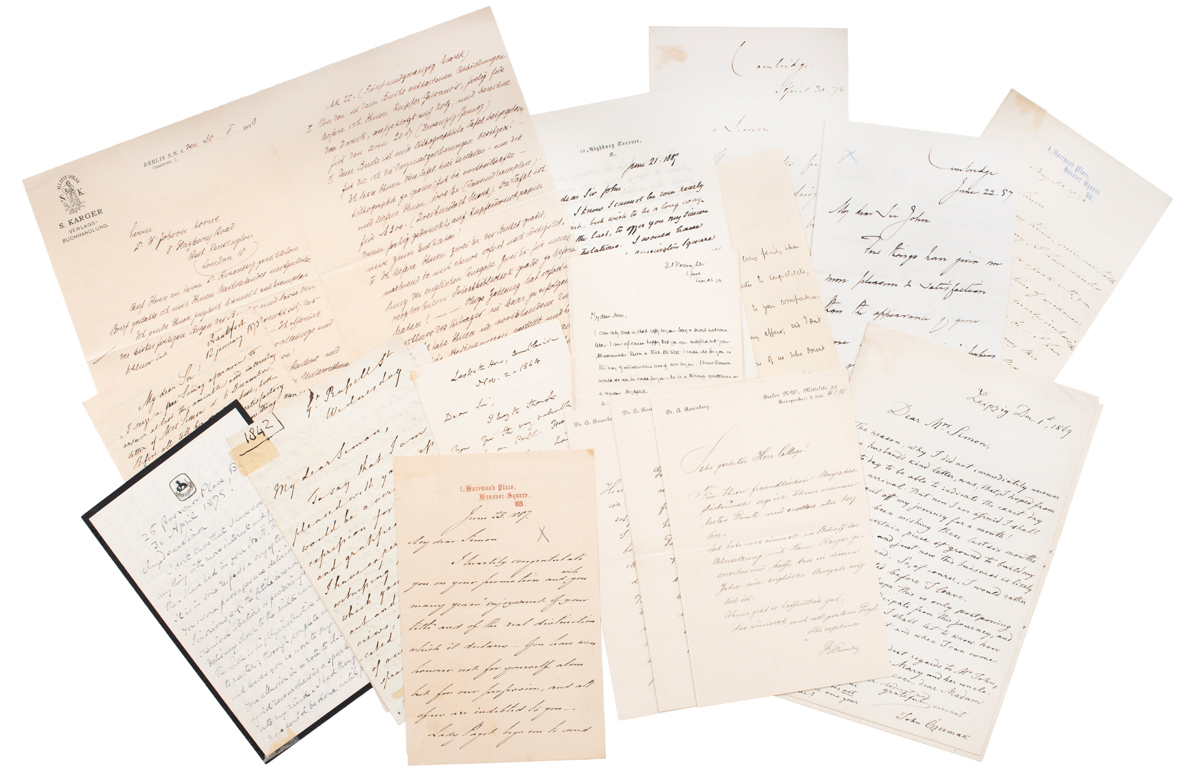

Many of the items in this volume are letters of congratulation received following Simon’s appointment as KCB in June 1887, from friends including: William Anderson, surgeon and collector, an ‘old pupil’ of Simon; Edward Ballard, public health reformer (‘That you may be spared yet many years to enjoy still more and more fully that esteem and affection of us all which you already possess, is [my] earnest hope’); George Buchanan, surgeon; Dr Alfred Haviland, pioneer of cancer research and mapping of epidemics; George Murray Humphry, Cambridge professor of physiology and anatomy (‘not many men have had the ability, the unselfishness & the high honour of character, as well as the opportunity, to render such good service in their generation’); John Marshall, surgeon; Sir James Paget, surgeon and pathologist (‘you have won honour not for yourself alone but for our profession, and all of us are indebted to you’); Richmond Ritchie, civil servant; Max Simon, nephew (also writes of Jubilee celebrations in Ramsgate – fireworks, swimming races, ‘fighting in tubs’ and walking ‘the greasy pole’).

Other letters include:

Baron Coleridge, February 1882, regarding an article he had written which he felt, with hindsight, was unfair to Simon.

John Czermak (Hungarian laryngologist), December 1869, postponing his visit to London; again, in December 1872, recounting a bout of depression brought on by struggles with his laboratory and amphitheatre and his travels in search of recovery, including a brief study of ‘Hypnotism in animals’.

John Davy (chemist), November 1864, writing to thank Simon for sending his report on public health which ‘has interested me very much’.

Joseph Henry Green (physician and Simon’s teacher at St Thomas’s) writing, possibly in 1842 to congratulate Simon on a recent essay.

Sir Henry Holland (physician), thanks for Simon’s lectures on pathology, and disagreeing with Simon’s suggestion of the means of transmission of cholera: ‘I have acquired a more certain persuasion that organic matter at least, is concerned in the origin and propagation of the disease, I think more probably animal life than vegetable’.

Richard William Jelf (Principal of King’s College London), November 1849, thanks for Simon’s Report: ‘the most remarkable Document that has appeared for many years’.

Sir George Edward Paget (physician), April 1875, thanks for Simon’s Reports: ‘Every year’s experience adds strength to my conviction that the causes and prevention of disease are incomparably the most worthy of all medical studies. You will be remembered as a benefactor of humanity.’

Sir James Paget (surgeon and pathologist), May 1870, regarding the need for reform of public health policy: ‘Sanitary affairs – in your absence – would be the least cared-for of all the duties of a government: letters and telegraphs would be more looked-after than lives, because for those there is a complete machinery, for these there is one man who will be, but is not, immortal’. He also complains of great overwork.

L.H. Stone (Treasurer at St Thomas’s), June 1881, replying to Simon’s resignation letter: ‘Your advice and counsel in all matters connected with the administration of the affairs of the Hospital … have been to me most invaluable and especially your suggestions both verbal and written in connection with the scheme for the admission of Paying Patients – suggestions which enabled the scheme to become acceptable to the staff as well as the Government.’

Georg Varrentrapp (German doctor with a particular interest in hygiene), several letters including one of May 1872, inviting Simon to a congress of German naturalists and physicians which was to have a section on public health, and writing of a proposed trip to London to see ‘some works of sewerage and irrigation, good new hospitals … normal barracks and other constructions important by their hygiene arrangements’ and to meet with ‘Miss Nightingale, Captain Douglas, Galton’ and others. Also January 1873, expressing concern about Simon’s eye problems and instructing him to rest and get proper medical care to ensure his recovery: ‘You are very important for our young science, public health; you must work a great deal more in that matter’.

Sir Thomas Watson (physician), April 1878, suggesting arsenic as a treatment for cancer: ‘There seems to be good evidence that the human body may be brought to bear considerable, even large, quantities without danger to life or detrimental to health’.