[DEFOE, Daniel.]

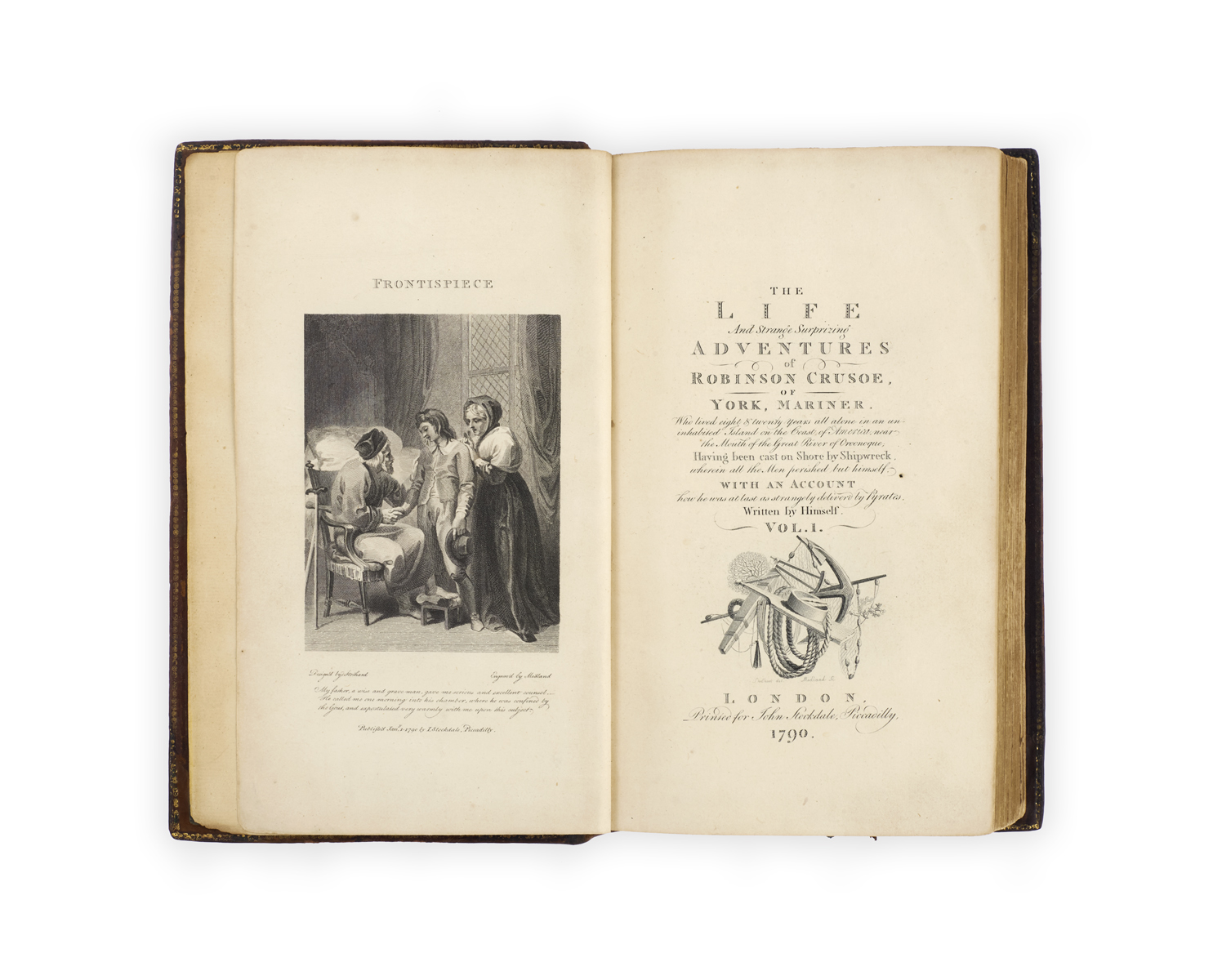

The Life and strange surprizing Adventures of Robinson Crusoe, of York, Mariner …

London: Printed for John Stockdale … 1790.

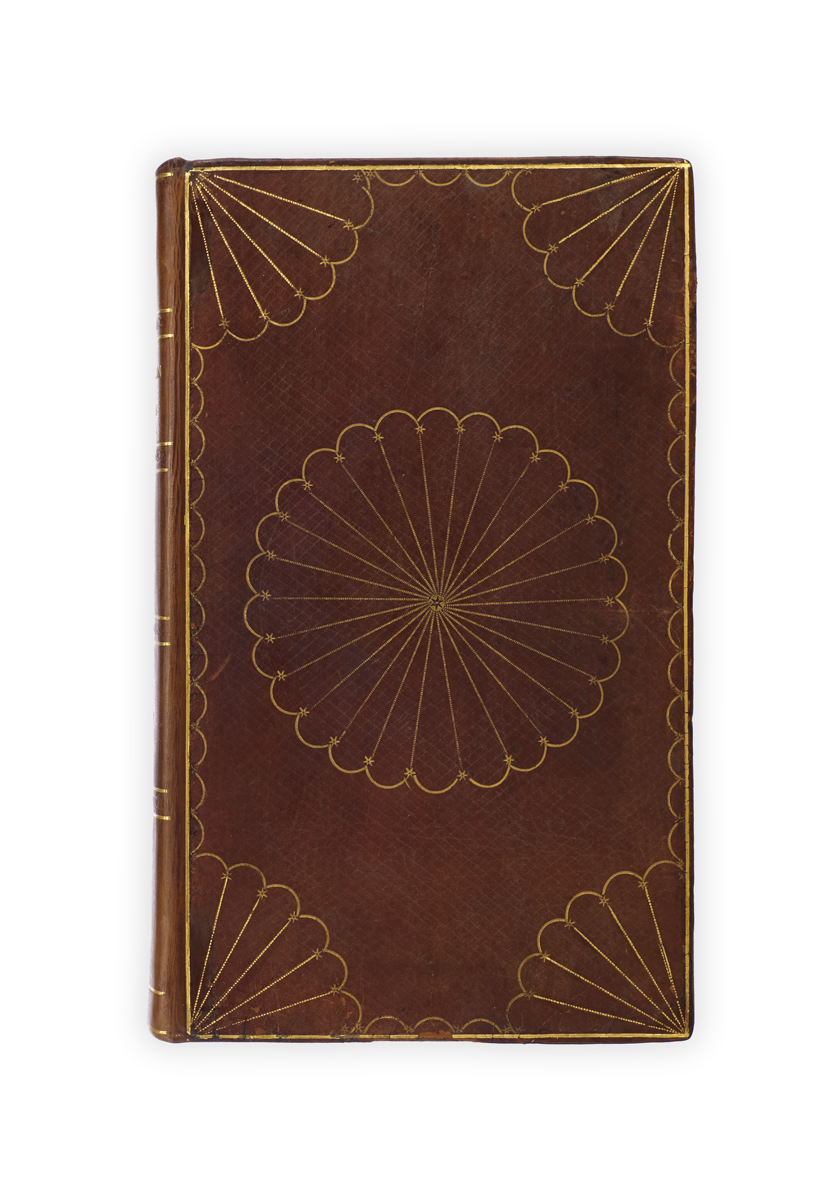

Two vols, 8vo, pp. [20], 389, [1]; v, [1], 456, [16 (advertisements, with a terminal blank)]; with engraved frontispieces and title-pages and 12 engraved plates by Medland after Stothard, tissue guards; the ‘Life of Daniel Defoe’ has a separate title-age and frontispiece (register and pagination continuous); extra-illustrated with 13 contemporary original drawings in pencil, pen and colour wash, each within a black border; some offset from the black borders else a very good copy in early nineteenth-century diced russia, the covers gilt with a large scalloped central wheel and cornerpieces, neatly rebacked and recornered; armorial stencil to front endpapers of William John Church.

Added to your basket:

The Life and strange surprizing Adventures of Robinson Crusoe, of York, Mariner …

First Stockdale edition, a unique copy, augmented with an evocative suite of original illustrations.

Stockdale’s Crusoe ‘was an important contribution to the life of Defoe’s book. The handsome set restored the Crusoe text, which, by 1790, had been much abused. George Chalmer’s Life of Defoe [first 1785] was the first significant biography of Defoe,’ while Thomas Stothard’s ‘extensive and beautiful illustrations made Stockdale’s the first edition so finely decorated’ (Lovett 89).

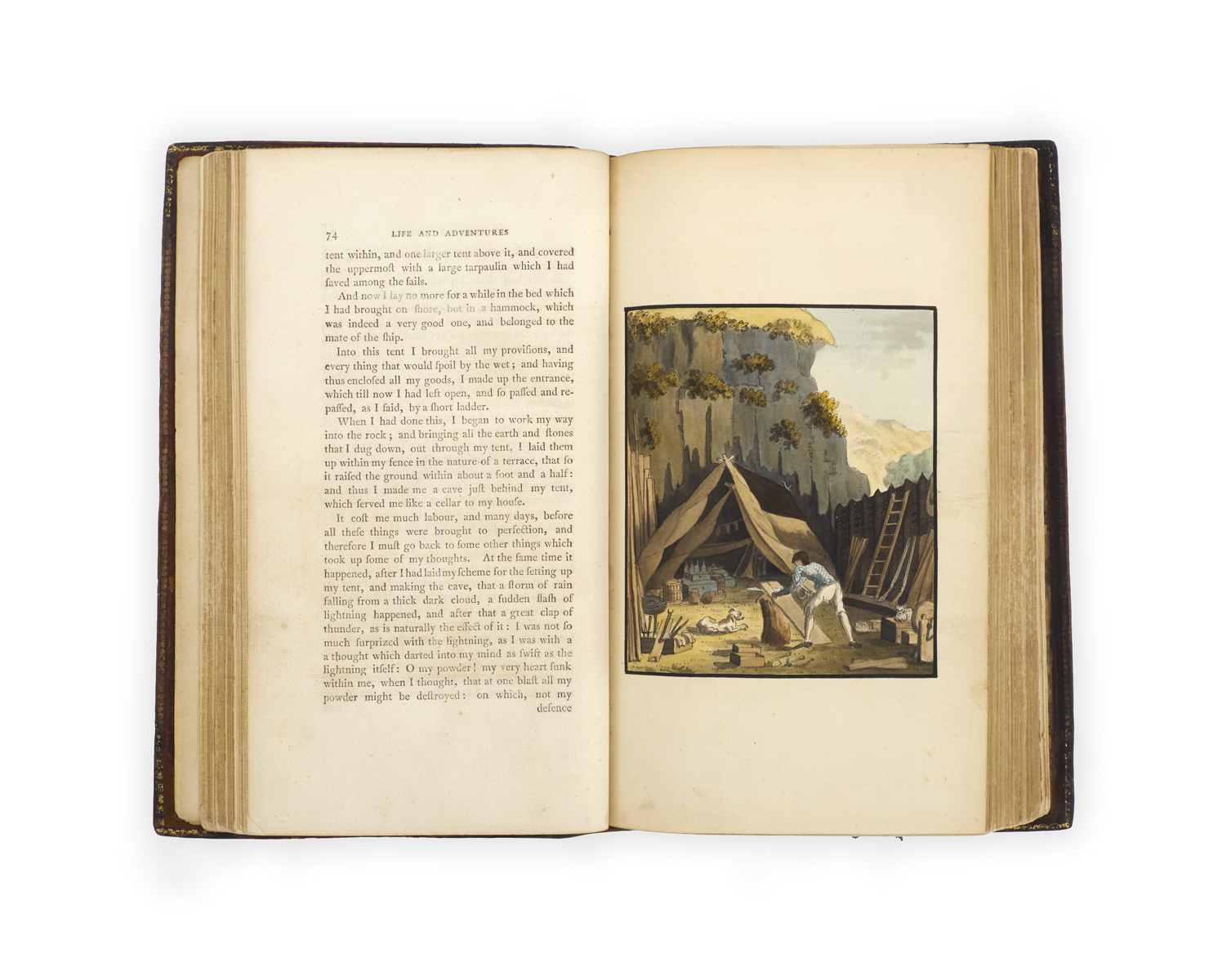

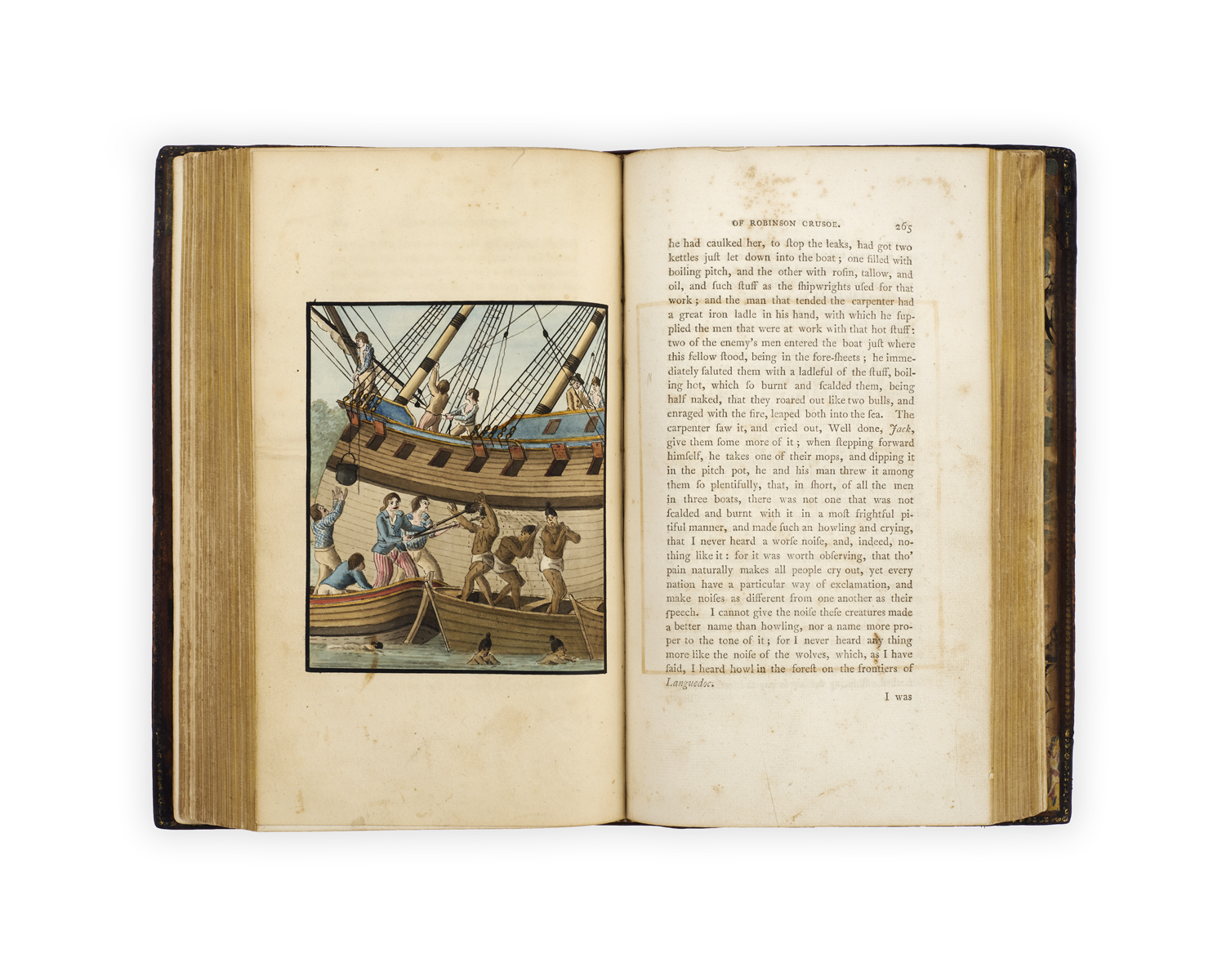

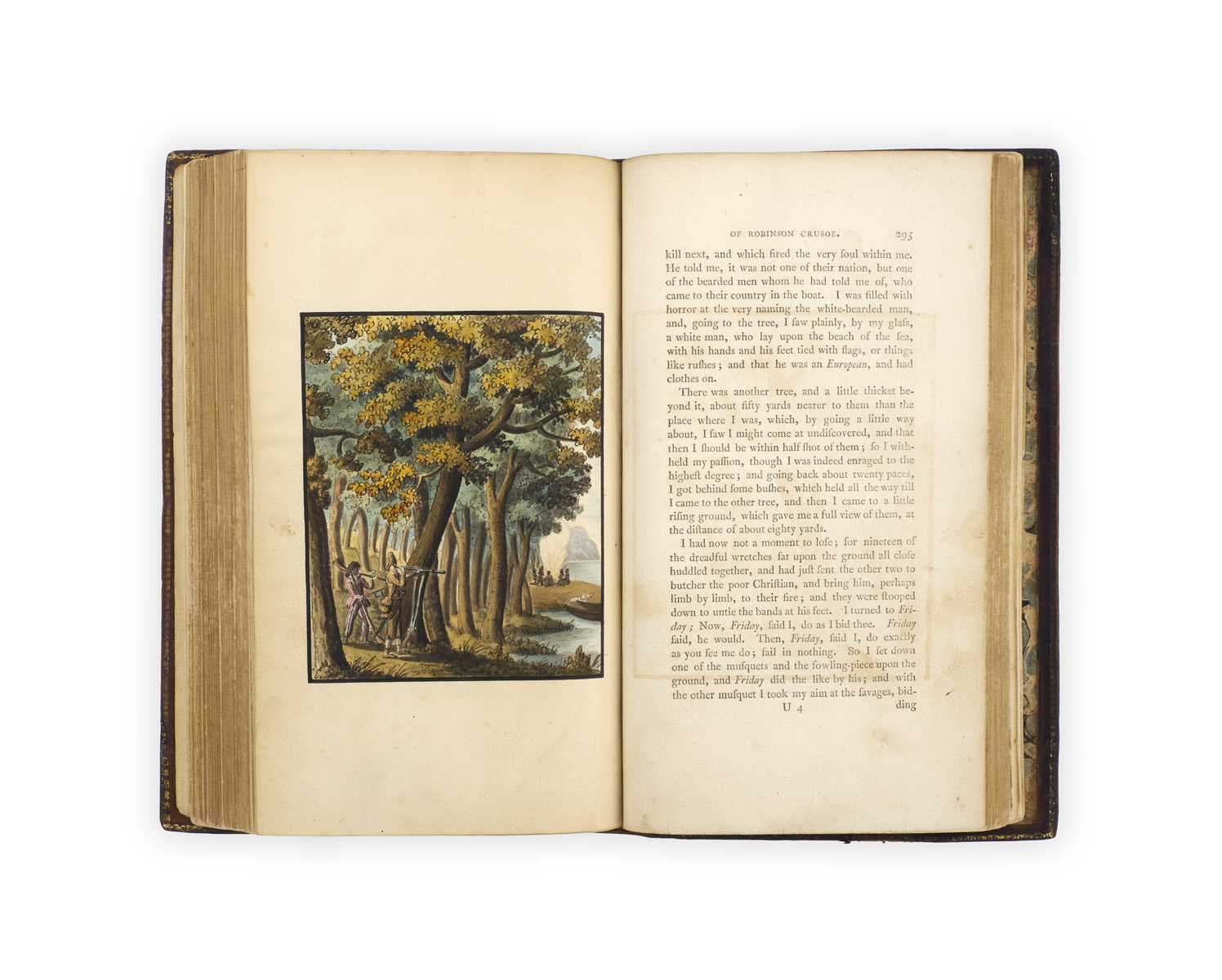

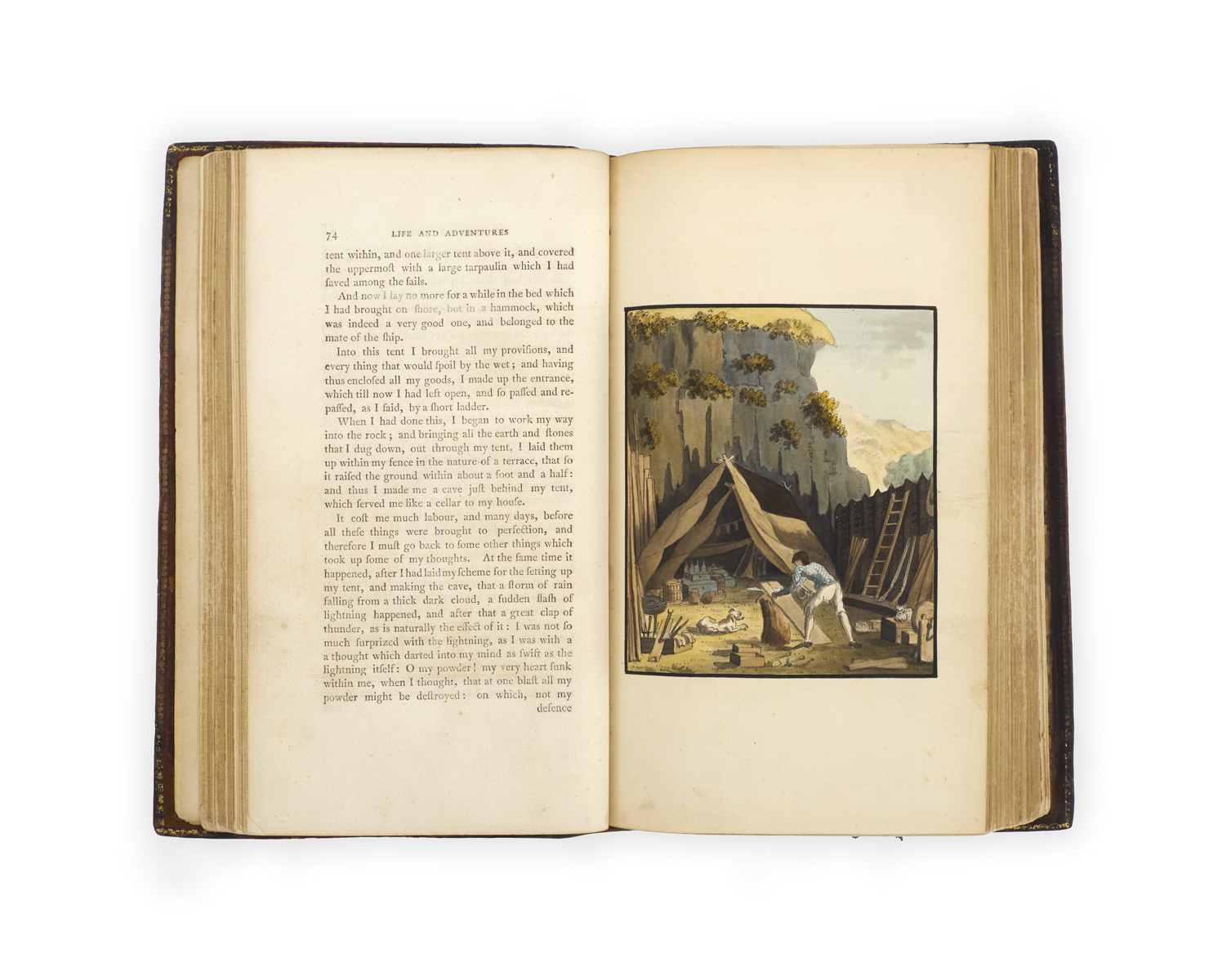

Stothard had first illustrated Crusoe with a set of seven images in The Novelist’s Magazine (1781), described by Austin Dobson as the beginning of English book illustration ‘by imaginative composition’. For the Stockdale edition, he produced a new set, engraved by Thomas Medland – ‘a more comprehensive series … the first pictorial treatment of Robinson Crusoe as a progress’ (Blewett) – and they paved the way for numerous illustrated editions to follow. They show an industrious, domestic Crusoe, sociable with Friday and the Spanish soldier they rescue, and the plates are dominated by the human protagonists. In contrast the anonymous illustrator here shows a Crusoe more overwhelmed by his surroundings, which are rendered in lush tropical colour, and threatened by those he encounters; he unloads stores from the shipwreck, constructs shelters, is surprised by a goat in a cave, navigates his canoe to the Spanish wreck. In the first four images he is in jaunty checked shirt, which gives over thereafter to his trademark furs and hat. Friday appears in two images, first in red stripes, as he and Crusoe fire on the cannibals; and then playing with the bear up a tree, a popular scene clearly derived from the Stothard’s illustrations of 1781, but which was omitted in 1790. Stothard’s images for the Further Adventures are rather static conversation-pieces with multiple figures. Our talented illustrator includes instead several dramatic scenes of boats, and of conflicts with ‘savages’, as a well as a Chinese potentate under an umbrella.

See Blewett, The Illustration of Robinson Crusoe (1996).