CHANSONS OF THE 1790s

[CHANSONS.]

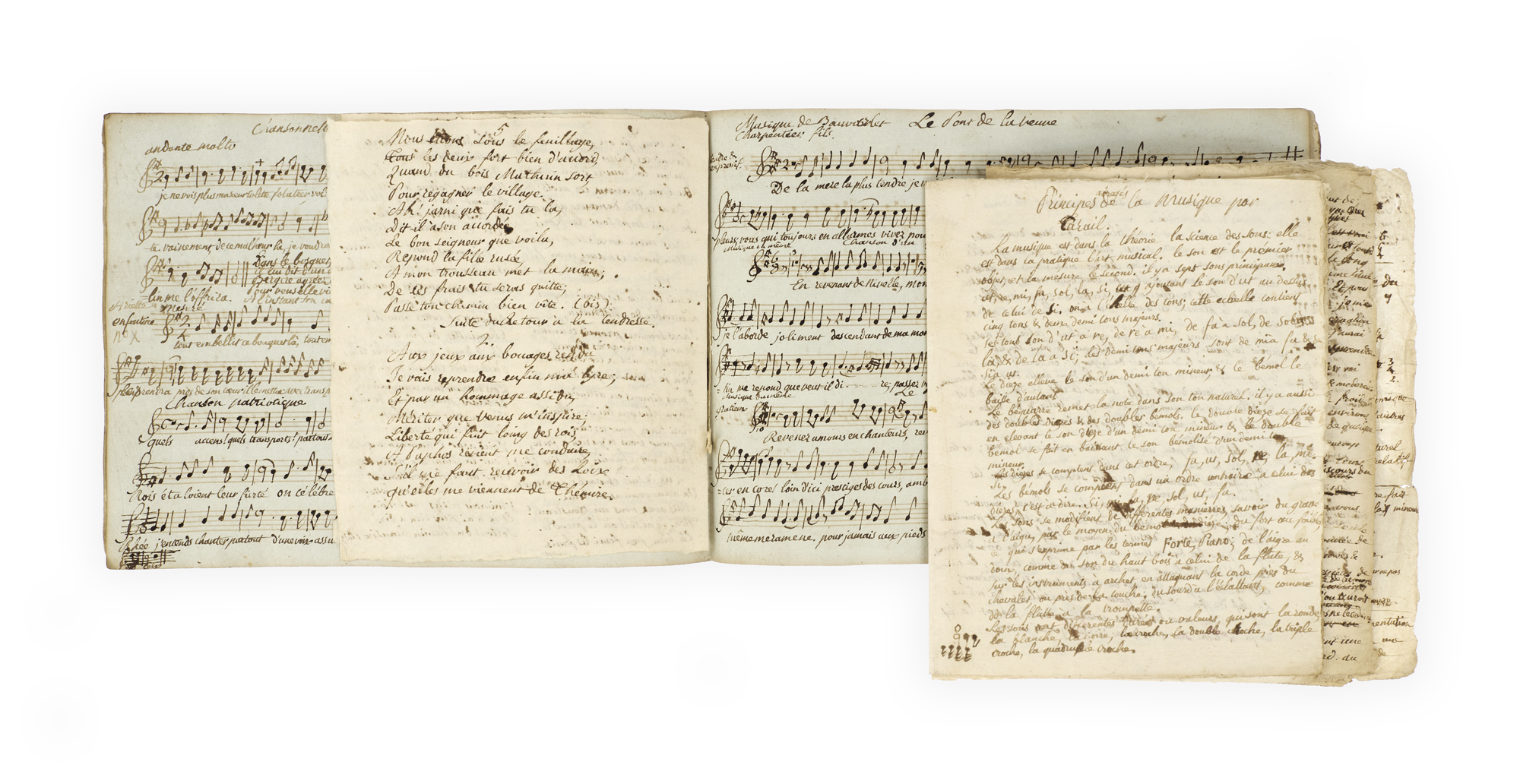

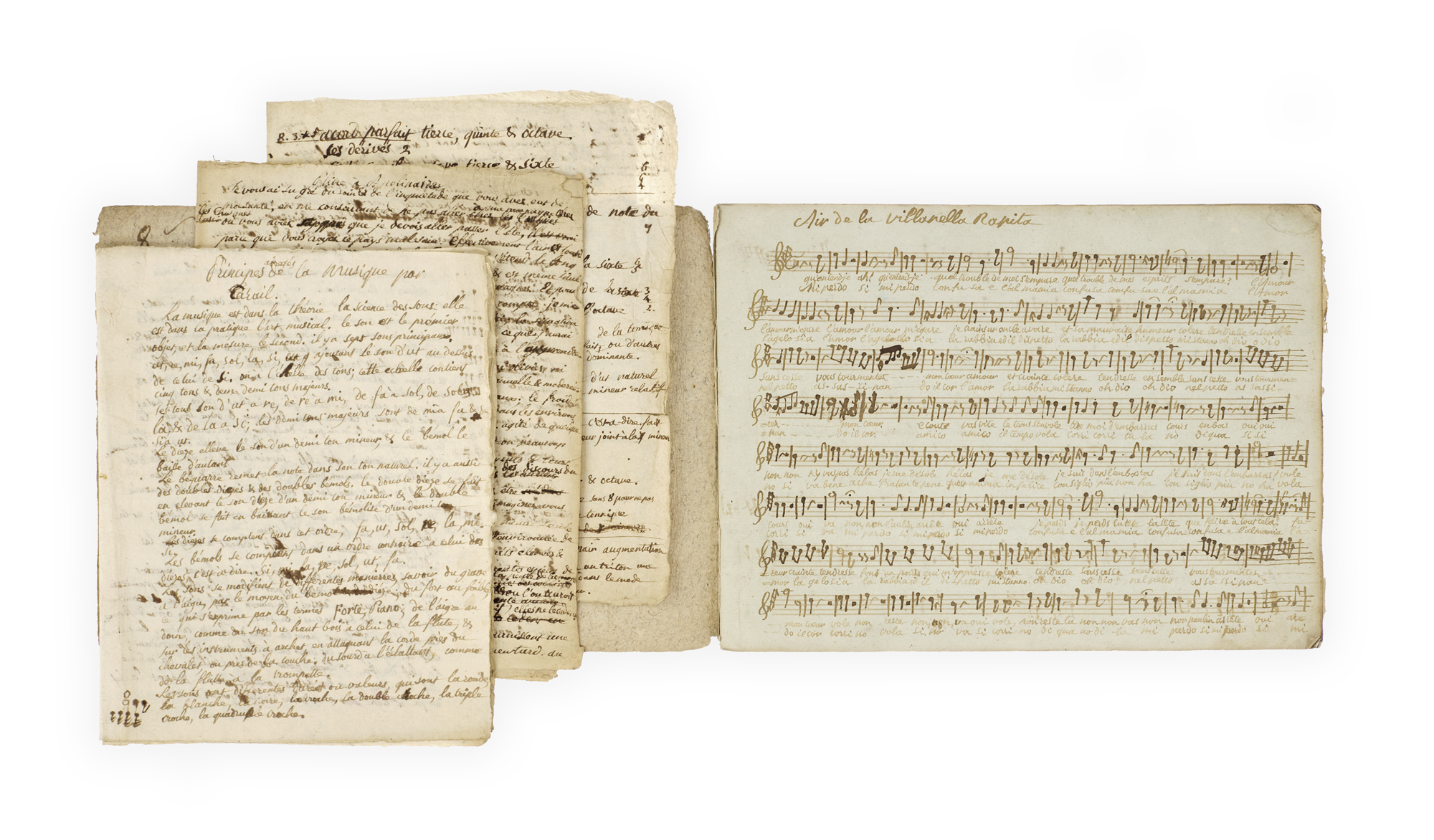

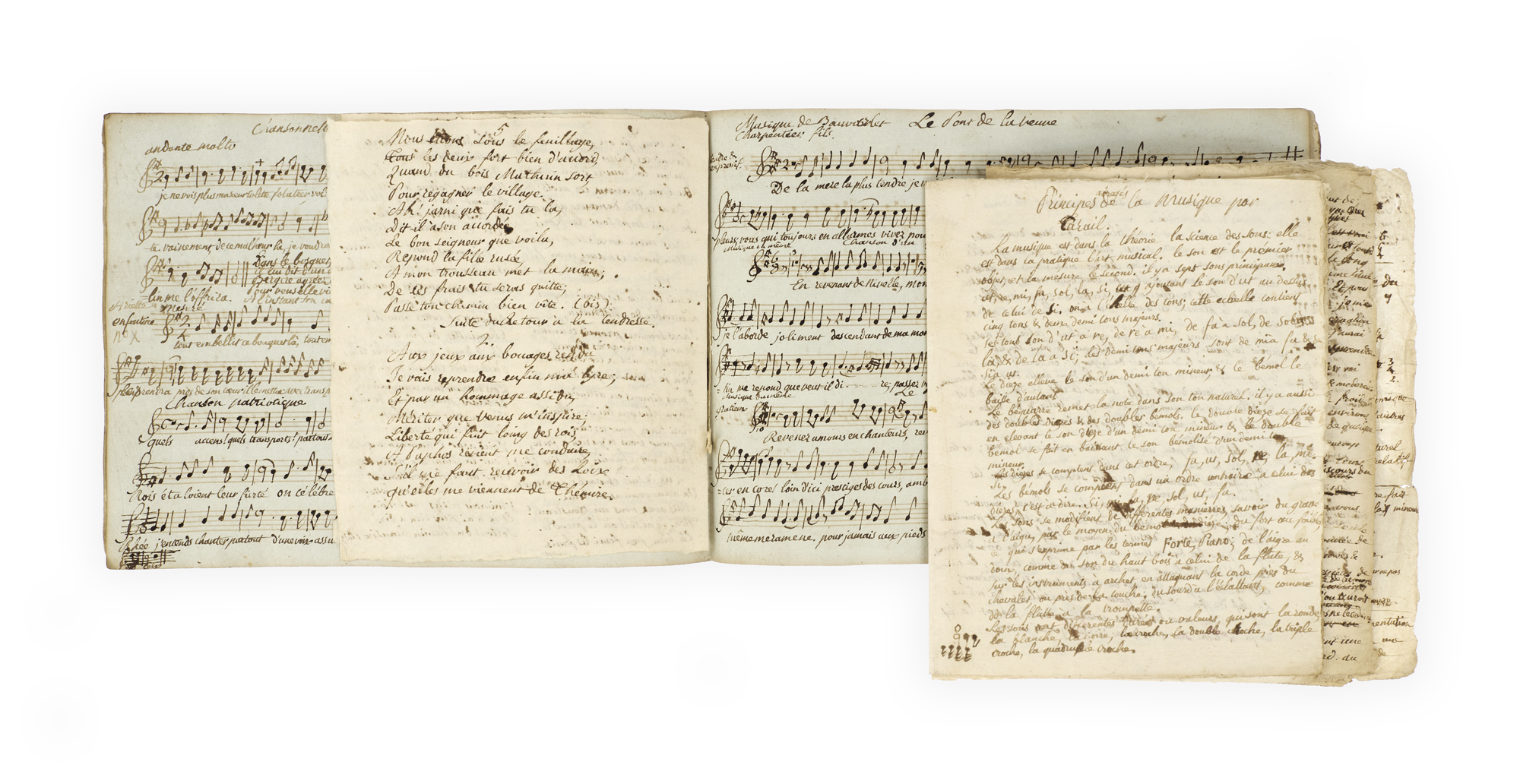

Manuscript collection of arias, chansons, and romances, including pieces by Bianchi, Bruni, Paisiello, Beauvarlet-Charpentier fils, Jean-Baptiste Roche etc. Along with a manuscript ‘Principes abregés de la Musique par Tarail’. France (Nantes?),

c. 1795.

Oblong 4to, 15 leaves, manuscript staves, one (occasionally two) system; some songs with the text of additional verses interleaved or inserted on smaller sheets; the ‘Principes abregé’ on 8 leaves, quarto, laid in loose, along with a draft French translation of a letter from Pliny to Apollonius (4 leaves, heavily corrected); edges slightly thumbed, but generally in good condition in contemporary marbled paper wrappers.

Added to your basket:

Manuscript collection of arias, chansons, and romances, including pieces by Bianchi, Bruni, Paisiello, Beauvarlet-Charpentier fils, Jean-Baptiste Roche etc. Along with a manuscript ‘Principes abregés de la Musique par Tarail’. France (Nantes?),

A fascinating manuscript collection of French songs, both operatic and popular, compiled in the years after the Thermidorean Reaction and the execution of Robespierre.

The arias, in Italian and French or French alone, are taken from works including La Villanella Rapita (staged Paris 1789) by Bianchi, L’isle enchantée by Bruni (1789), La soirée orageuse (1790) by Dalayrac, and Nina, Il Barbiere di Sivigila, and La Molinara by Paisiello.

More unusual are the chansons and romances, mordant in tone, which circulated in the latter half of the 1790s in lamentation of the greater excesses of the Revolution; ‘Complainte de Montjourdain’ (not the setting by Adrien published in 1795) and ‘Couplets fait par Duval pendant sa detention’, for example, deal with specific figures executed in 1794, while more generic works like ‘A ma femme le jour de sa mort’ and ‘Complainte de la jeune epouse d’un detenu’ express a degree of social reckoning. We cannot trace printed sources for most of these.

‘After waning during the early 1790s, the French vocal romance experienced a resurgence following the Terror, albeit in a form different from the one it had taken before the Revolution. Advocated by Jean-Jacques Rousseau, the early romance was known for its simplicity and bucolic charm. It naïvely related comic and sentimental tales from the distant past. In the latter half of the 1790s, however, French romances began to reflect the turmoil of the revolutionary era. They continued to be relatively simple strophic songs composed as amateur entertainments and as numbers in opéras comiques, but their musical language became graver and more sophisticated. Their accompaniments grew more expressive, and they drew on the Sturm und Drang movement in order to convey bleaker subjects’ (Myron Gray, ‘Musical Politics in French Philadelphia, 1781–1801’, 2014, Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 1292).

Also included are at least five pieces by the organist Jacques-Marie Beauvarlet-Charpentier (1766–1834), who ‘rode comfortably through the political upheavals’ of the 1790s (Grove), and a group of seven ariettes, a duo, and a chansonette attributed to ‘J. B. Roche’. These are numbered, though not included in number order, suggesting a printed source. A likely candidate is the Jean-Baptiste Roche described in Annales nantaises (1795) as the author (‘vivant’) of a work on orthography and ‘un receuil de Pieces fugitives, en prose et en vers, avec musique’ [1780].

The ‘Principes abregés de la Musique par Tarail’ is a cursory summary of the basics of music theory. Jean-François Tarail (1735–1812) was organist of the Collégiale Notre-Dame de Nantes (until its closure by revolutionary authorities in 1793), but no such work is known by him. The conjunction of both Roche and Tarail suggest Nantes as the place of compilation, perhaps by a student of Tarail.