THE MOST FAMOUS ILLUSTRATED BOOK

OF THE ITALIAN RENAISSANCE

[COLONNA, Francesco.]

Poliphili hypnerotomachia, ubi humana omnia non nisi somnium esse ostendit, atque obiter plurima scitu sane quam digna commemorat [La hypnerotomachia di Poliphilo, cioè pugna d’amore in sogno].

Venice, [heirs of Aldus], 1545.

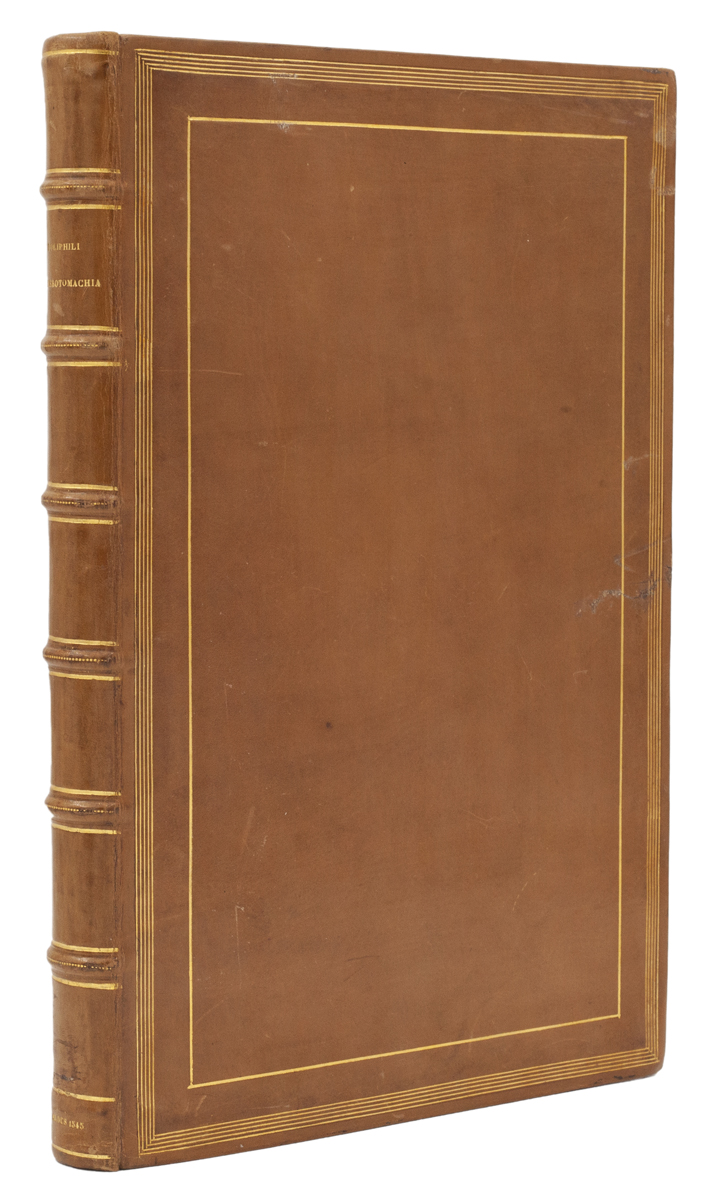

Folio (c. 303 x 201 mm), ff. [230 (of 234)]; a–y8, z10, A–E8, F4; 170 woodcuts in text, of which 9 full-page (the Priapic woodcut uncensored); woodcut Aldine device to verso of last leaf; n1v and n8r transposed (as in the first edition); bound without preliminary section [*]1–4; f. a1 very lightly foxed, but a very good, broad-margined copy, very lightly washed, bound in nineteenth-century polished calf, boards panelled in gilt, spine gilt-ruled in compartments, one lettered directly in gilt; a few scuffs; copper-engraved armorial bookplate (by Agry) of the family Nuñez del Castillo, marquesses de San Felipe y Santiago, to upper pastedown; twentieth-century bookseller’s ticket of Arthur Lauria to front free endpaper.

Added to your basket:

Poliphili hypnerotomachia, ubi humana omnia non nisi somnium esse ostendit, atque obiter plurima scitu sane quam digna commemorat [La hypnerotomachia di Poliphilo, cioè pugna d’amore in sogno].

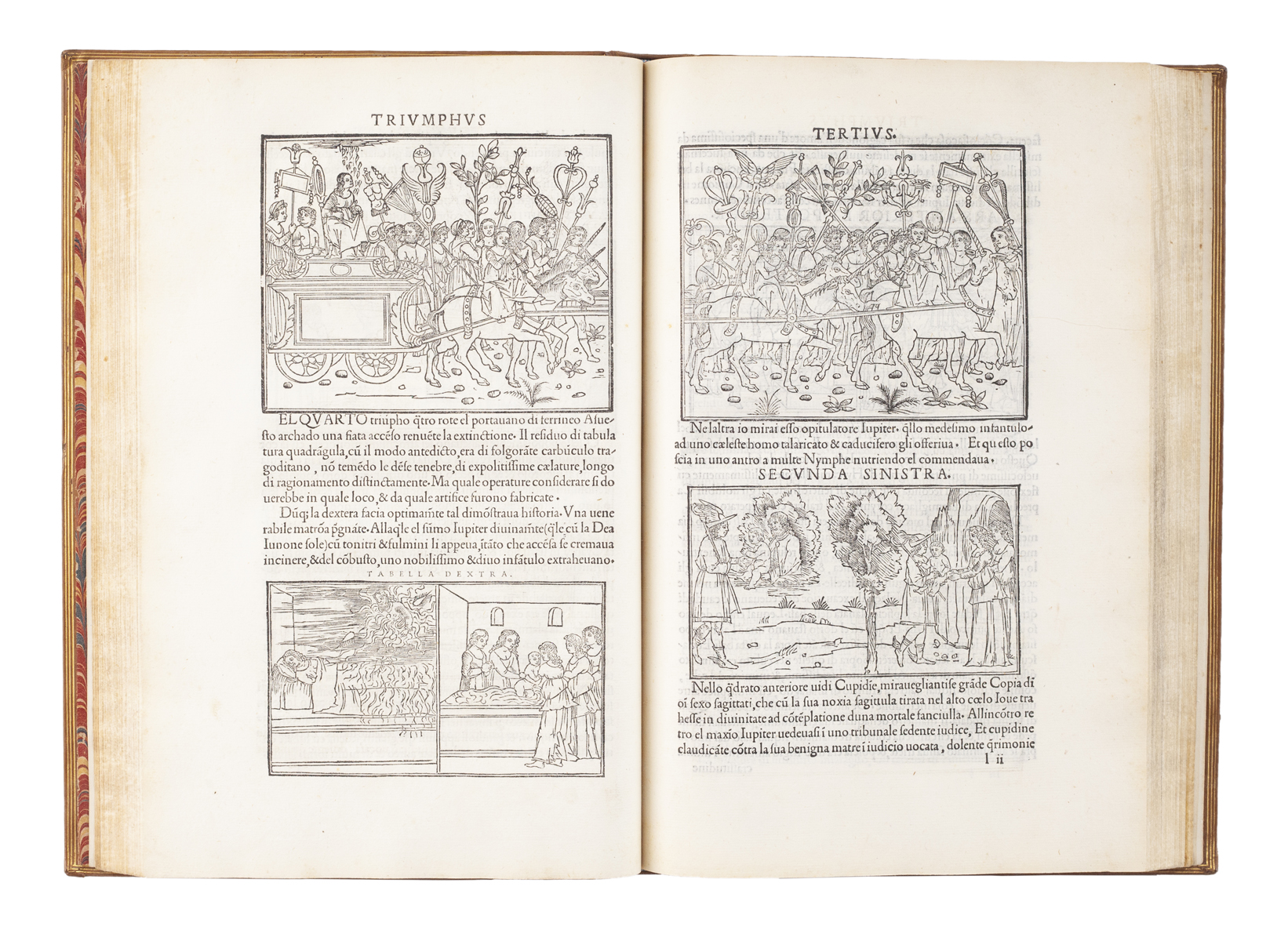

Second edition, scarcer than the first (also an Aldine, published in 1499), of the most beautiful illustrated books printed in Italy in the fifteenth century. Known for its fine woodcut illustrations, mysterious meanings, and the cryptic inclusion of Colonna’s name, the Hypnerotomachia has been celebrated as the finest example of early Venetian printing.

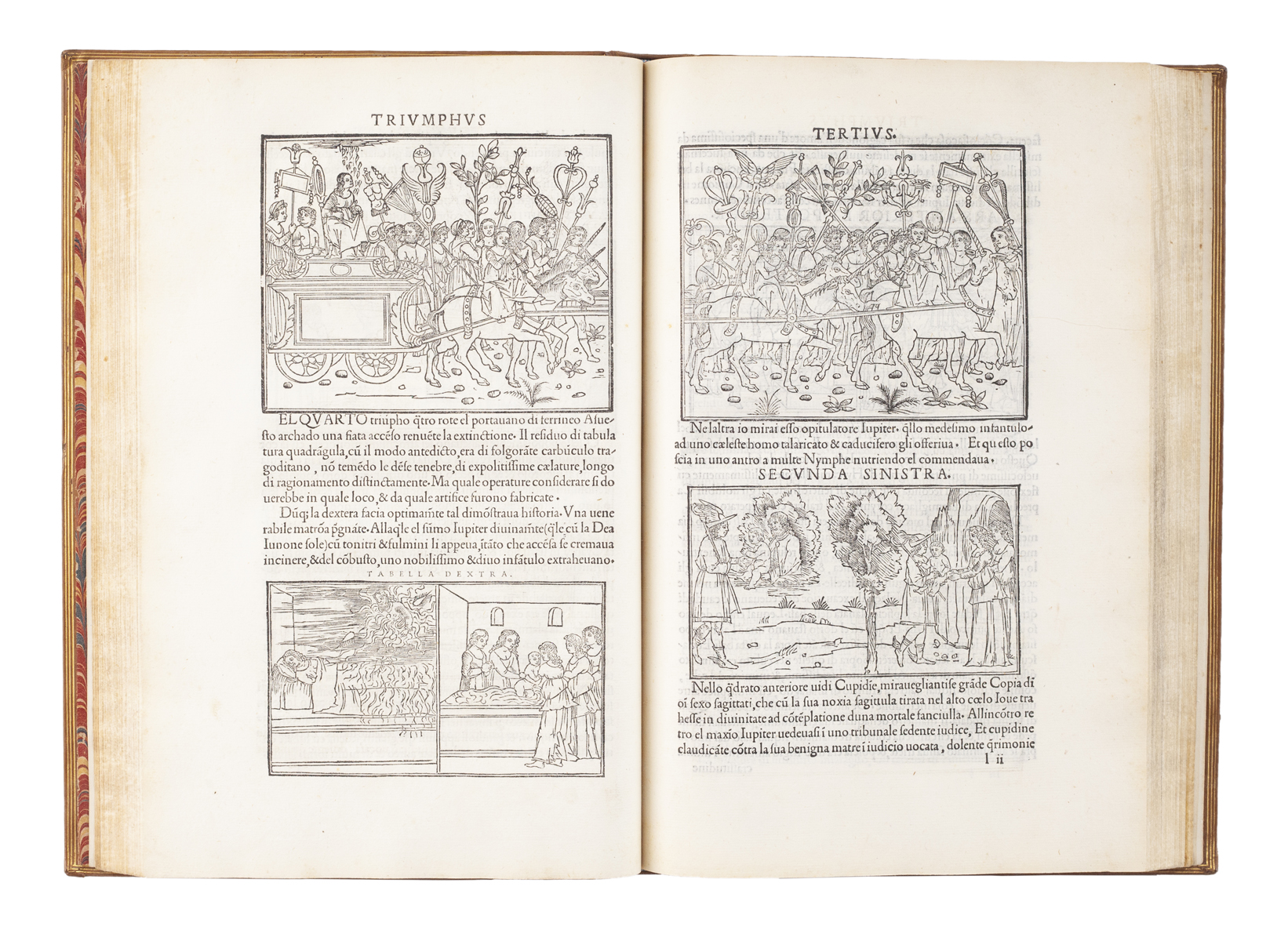

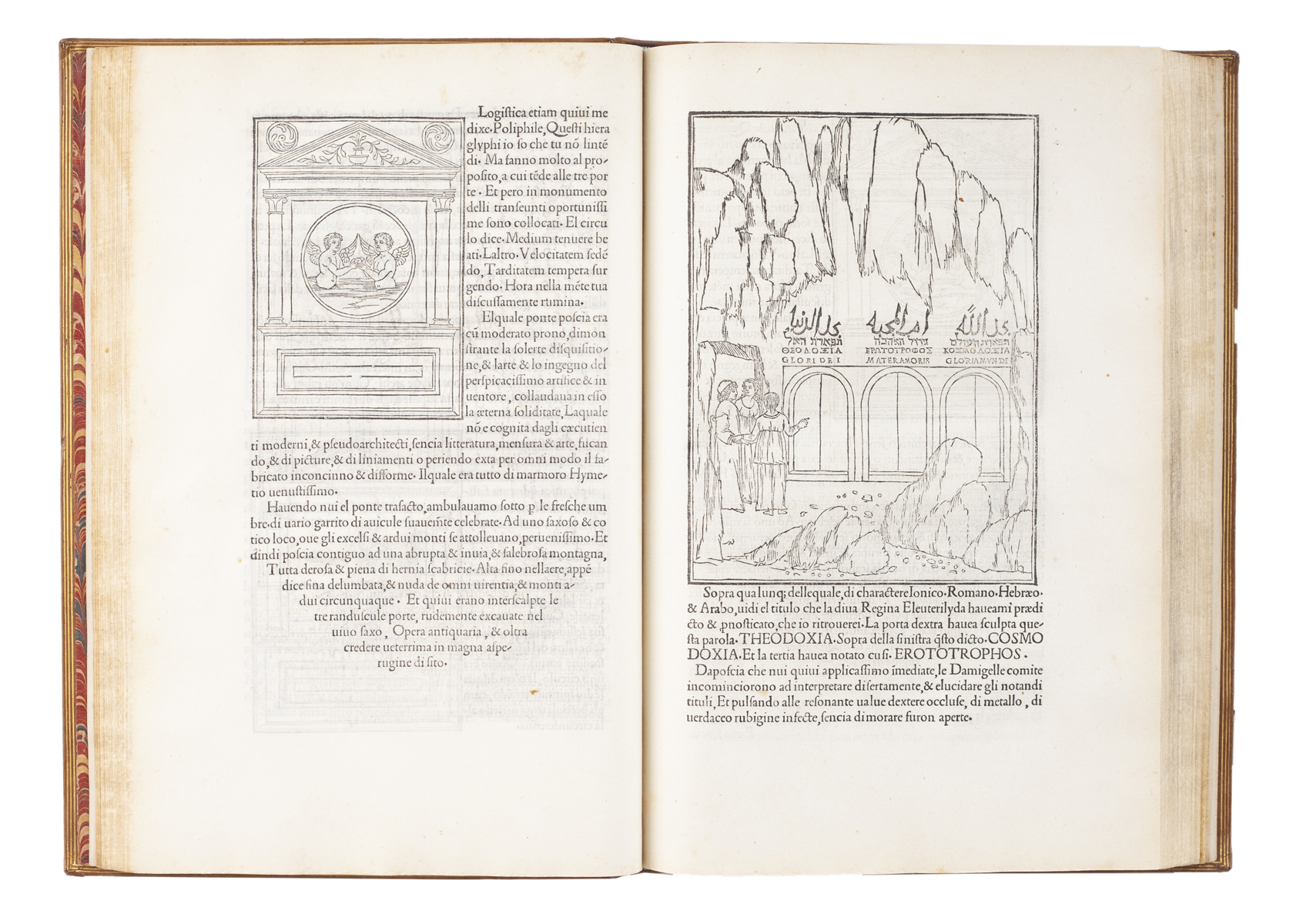

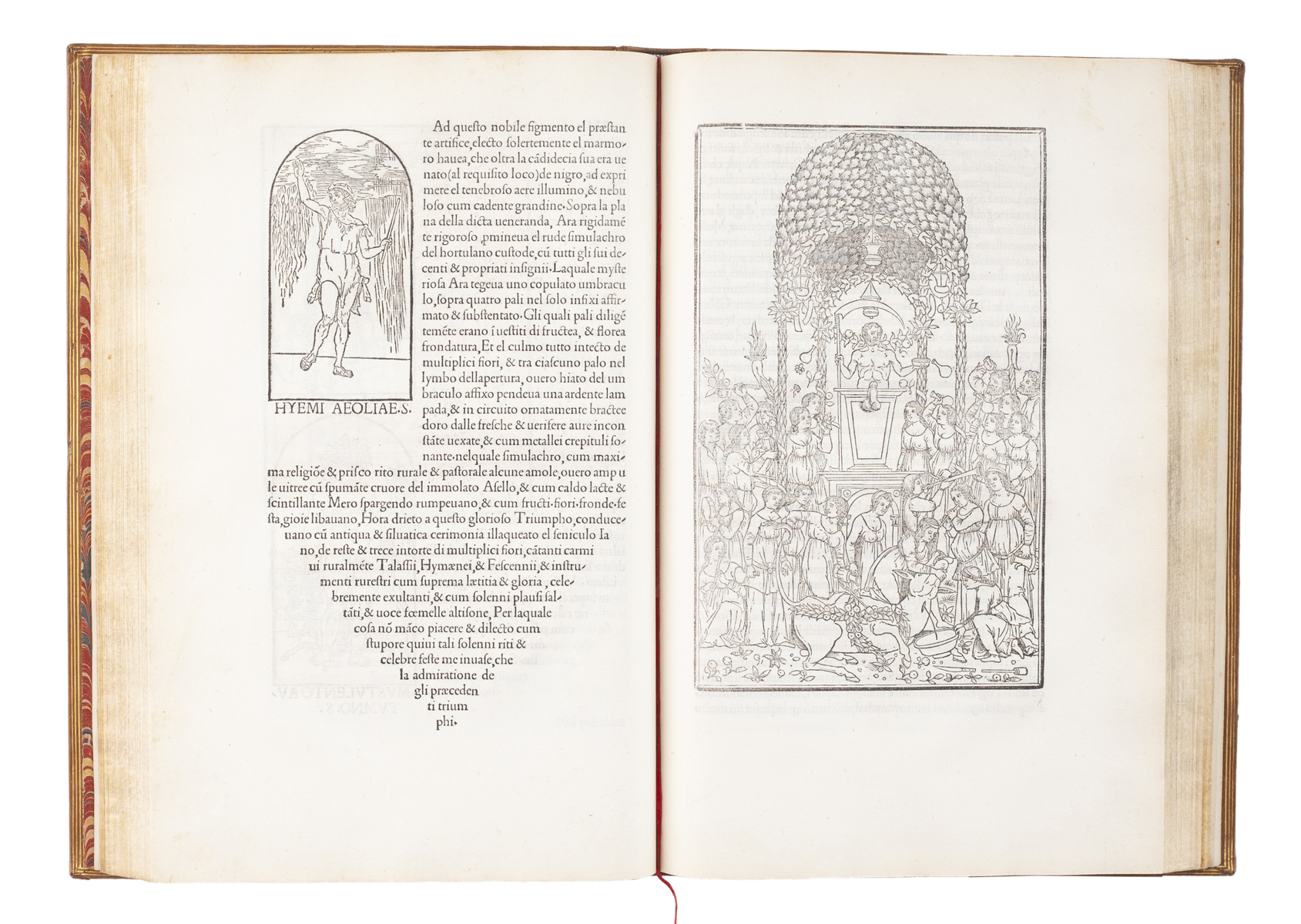

‘It is not easy to sum up in a few words the artistic and literary interest of the book. The woodcuts, one of which is signed “b” have been ascribed, as Pollard says, with no good reason to a dozen artists including Bellini. What is clear is that the artist who designed them was influenced by the work of Bellini, Carpaccio and perhaps Botticelli. They have a unique perfection and all that can be said with certainty is that the same hand may be traced in some other contemporary woodcuts. Why Aldus published this book is a mystery since he was mainly interested in producing editions of the Greek and Latin classics. In any case it was an expensive failure, for in 1508 he complains that nearly the whole edition was unsold and it was left to later generations of book collectors to appreciate it. Nevertheless, it was re-printed in 1545, published three times in French and translated into English in a botched version in 1592 under the title Hypnerotomachia or the Strife of Love in a Dream. It is a curious work written in a language which is a mixture of Latin and Italian [interspersed with Greek and Hebrew words], and briefly can be described as a Renaissance monk’s dream of the ancient world. “Poliphilo, the hero and lover of Polia, falls asleep and in his dream and pursuit of Polia sees many antiquities worthy of remembrance and describes them in appropriate terms with elegant style” – to quote the words of the preface’ (J. Irving Davis).

Nowadays the woodcuts are widely considered to be the work of Benedetto Bordone (1460–1531), a successful miniaturist active in Venice, turned cartographer and prolific designer of woodcuts later in life. ‘The illustration follows two themes, cuts relating to the story content of the dream and representations of ancient architecture, inscriptions, and triumphal processions observed by the dreamer and described in detail in the text’ (Ruth Mortimer, Italian 16th-century books, no. 131). The woodcuts of this edition are from the original blocks of the first edition, except for the six blocks on leaves b4v, b5r (two), e2v, e5r and x2r which were recut according to Ruth Mortimer. In fact, with the further exception of the first title being different, and the errata leaf at end not existing (the errors having been corrected) but its place taken by the register and colophon instead, it is a page-for-page reprint of the 1499 edition. The removal from the present copy of the title was perhaps a somewhat naive attempt to disguise this second edition as the first.

‘The author, Francesco Colonna (Latinized, Franciscus Columna) was a Dominican monk in the monastery of S.S. Giovanni e Paolo, who died in Venice, where he had lived the greater part of his life, in 1525 (or 1527) at a very advanced age. The last leaf in the book before the errata leaf [in the second edition, before the colophon], purposely hides the real author under the name “Poliphilus” but tells us the fact that the writing of the book was completed by said “wretched” (“misellus”) lover, at Treviso in May, 1467. It is on taking the first letter of each of the 38 chapters in succession, a device often resorted to in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, that we discover his identity in the phrase, “Poliam Frater Franciscus Columna Peramavit.” The identity of Polia, if she ever lived in real life, has never been established’ (Hofer, Variant copies of the 1499 Poliphilus, New York, NYPL, 1932, pp. 3–4).

Adams C2414; J. Irving Davis 85; EDIT16 12823; Essling 1199; Mortimer 131; Renouard 1545 14 (pp. 133–134); Sander 2057.