POEMS BY A LEADING SHAKESPEAREAN ACTRESS

'A WOMAN OF UNDOUBTED GENIUS' (COLERIDGE)

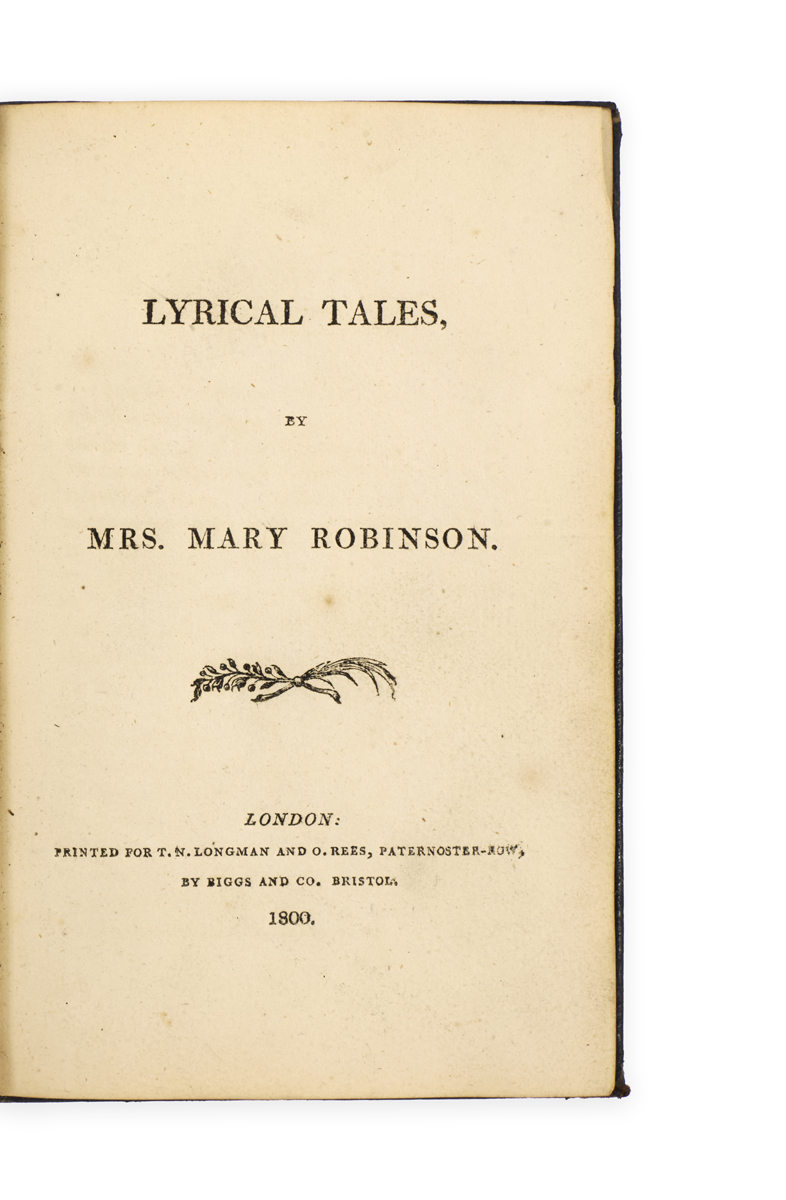

ROBINSON, Mrs. Mary (Darby).

Lyrical Tales …

London, Printed for T. N. Longman and O. Rees … by Biggs and Co. Bristol, 1800.

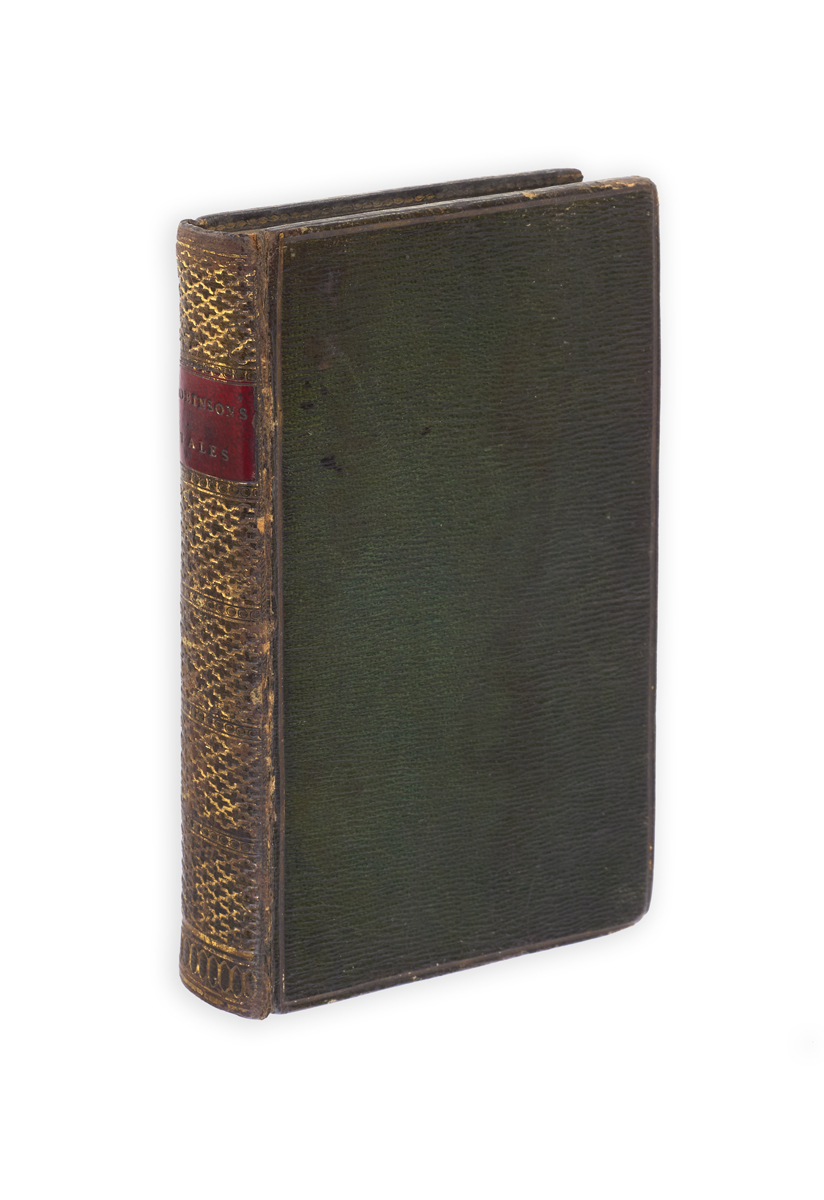

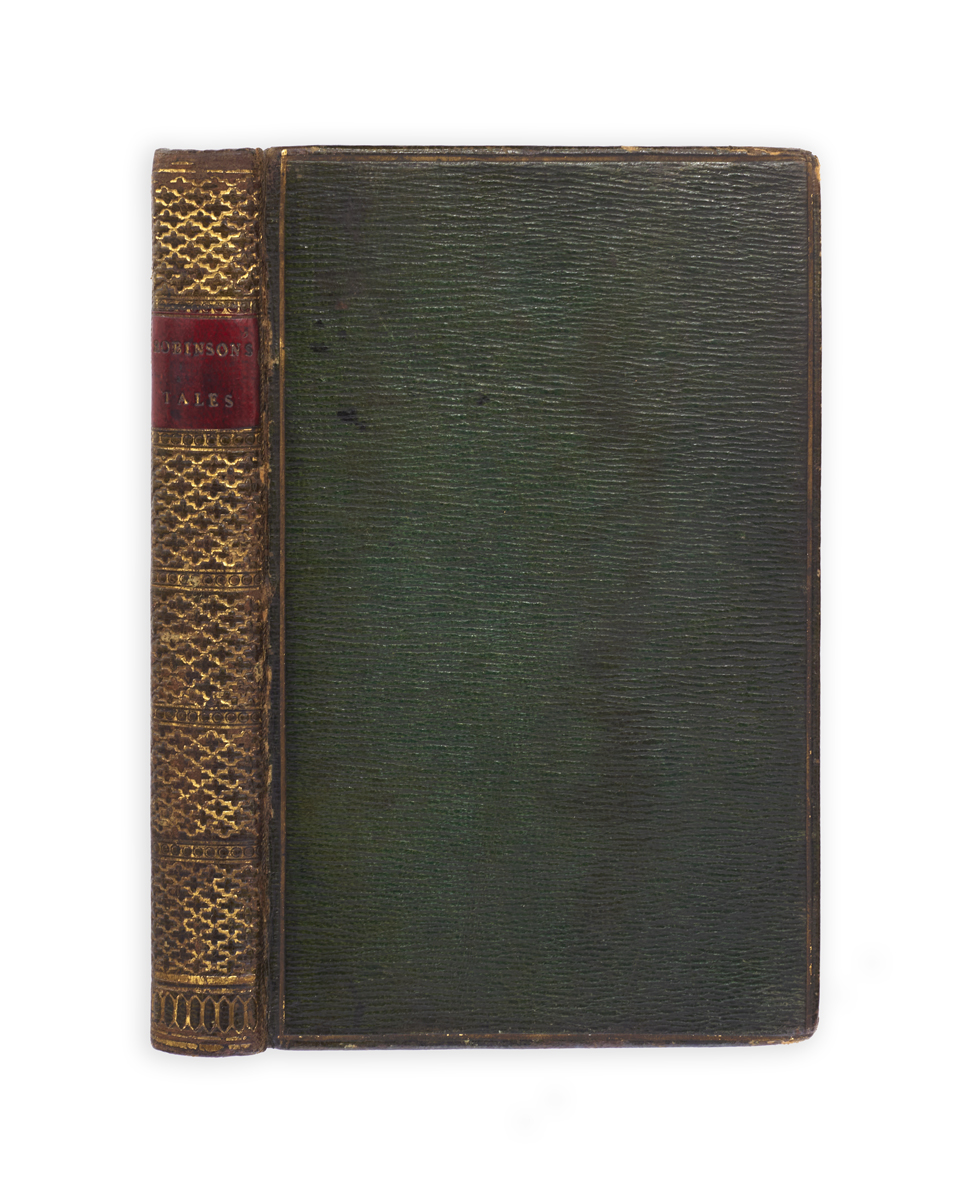

Small 8vo, pp. [4], 218, [2, advertisement leaf]; a portrait is found in some copies, but is not required and was never present here; a few spots and stains but a very good copy, in handsome contemporary green straight-green morocco, spine gilt to a lattice design, red morocco label, gilt edges, marbled endpapers (trace of old bookplate removed).

First edition, a revisionary response to Lyrical Ballads (1798) by the actress turned royal mistress turned author, Mary ‘Perdita’ Robinson, published only eight days before her death.

When Mary Robinson, the ‘English Sappho’, published her Lyrical Tales in December 1800, she was at the end of a long career and far more famous than Wordsworth or Coleridge – a product of her demimondaine reputation and her best-selling, and often strongly feminist, fiction. Since 1797 she had been in contact with Coleridge, a fellow writer on the Morning Post, and had come to feel increasingly drawn to the Lake Poets, both politically and aesthetically. The title of her Lyrical Tales clearly alludes to Lyrical Ballads, and also to Southey, whose own ‘lyrical tales’ have a visible influence. The opening poem, ‘All Alone’, is particularly notable, a reinterpretation of ‘We are Seven’ and ‘The Thorn’.

Robinson had been the leading Shakespearean actress of her day, and (briefly) mistress of the Prince of Wales, before a miscarriage left her crippled and she took to laudanum and literature. ‘A singularly brave writer’ (Jonathan Wordsworth), she became a close friend of Mary Wollstonecraft, and Coleridge was a fervent admirer. When he heard of Robinson’s final illness he was so upset that he consulted Humphry Davy about her condition and sent suggestions for medication, together with an early draft of ‘Kubla Khan’ and a poem to her entitled ‘A Stranger Minstrel’ (Wise, II, 69). Her response, ‘Mrs. Robinson to the poet Colridge’ [sic], published in volume IV of her posthumous Memoirs, 1801, contained the first extracts of ‘Kubla Khan’ to appear in print. Her early death at forty-three deprived English Romanticism of what may have become a major voice.

As Lyrical Tales were preparing for press, so was the expanded second edition of Lyrical Ballads, also printed for Longman by Biggs in Bristol. Wordsworth was concerned by the similarity of title and wanted to rename the volumes Poems; in the event the Lyrical Ballads were not published until late January 1801 despite the date on the title-page. Robinson’s reputation was useful to the Lake Poets, a fact of which Longman was well aware: the advertisements at the end of Lyrical Tales list Southey’s Poems, the two-volume Annual Anthology (Coleridge had requested Robinson’s inclusion), the as-yet unpublished second edition of Lyrical Ballads, Coleridge’s Poems 1797, etc.

Jackson, Romantic poetry by women, p. 278; Johnson, Provincial poetry, 770. Ashley J. Cross, ‘From Lyrical Ballads to Lyrical Tales: Mary Robinson’s Reputation and the Problem of Literary Debt’, Studies in Romanticism 40: 4 (2001); Jonathan Wordsworth, Ancestral Voices: Fifty books from the Romantic Period (1991).