THREE POLITICAL PAMPHLETS ENCOMPASSING SABBATARIANISM, HOME RULE AND THE WEST LOTHAIN QUESTION, AND

VICTORIAN POLITICS.

A Sammelband of three pamphlets, comprising:

A Sammelband of three pamphlets, comprising:

(i) John TYNDALL. The Sabbath. Presidential Address to the Glasgow Sunday Society Delivered in St Andrew’s Hall October 25, 1880. London, Spottiswoode and Co. for Longman, Green, and Co., 1880. 8vo (210 x 136mm), pp. 48; a few light spots; original printed upper and lower wrappers; wrappers a little spotted and marked, otherwise a very good copy. First edition in book form.

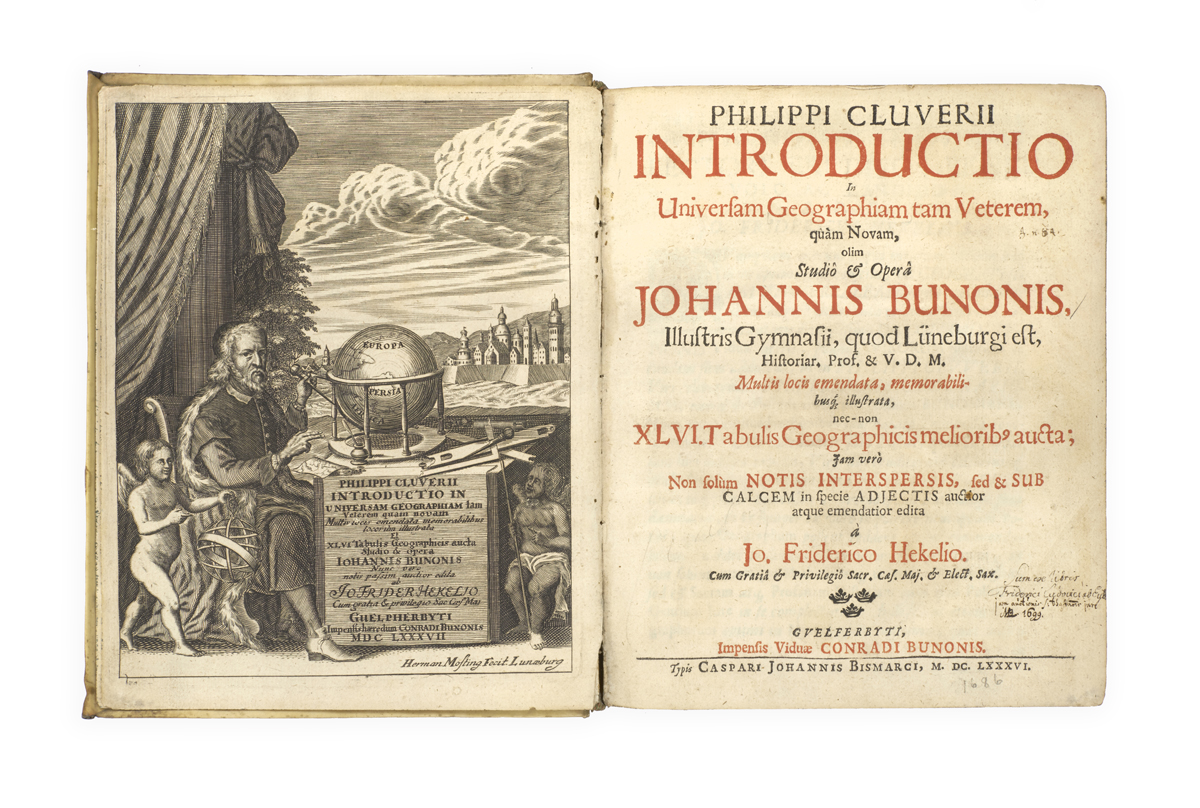

(ii) Robert WALLACE. Irish Usurpation in British Politics (Revised and Authorised Report.) Speech Delivered ... in Committee of the House of Commons, on July 12th and 13th, 1893. London, Colston & Company for The Temple Company, [?1893]. 8vo (212 x 136mm), pp. 16; variable light spotting; original printed upper and lower wrappers; wrappers spotted, otherwise a very good copy. First and only edition. Very rare.

(iii) William Edward Hartpole LECKY. Introduction to Democracy and Liberty ... Reprinted from the Cabinet Edition. London, Longmans, Green, and Co., 1899. 8vo (212 x 136mm), pp. lv, [1 (blank)]; a few light spots; original printed upper and lower wrappers; wrappers a little spotted, otherwise a very good copy. First separate edition.

Three works bound in one volume, early 20th-century English half polished calf gilt over cloth by Bickers & Son, London, spine gilt in compartments and lettered directly in three, patterned endpapers, top edges gilt, brown silk marker; extremities minimally rubbed, spine slightly faded, endpapers slightly spotted; provenance: Arthur E. Clementson, 19 April 1911 (pencilled inscription on front flyleaf, noting that the volume was bound by Bickers; The Sabbath with further inscription on upper wrapper dated 18 January 1881).

A Sammelband of three late-nineteenth-century British political works, bound up for the owner by Bickers. The first item, The Sabbath, is by the scientist John Tyndall (1820-1893), and was an address delivered to the Glasgow Sunday Society in his capacity as president. The Society was formed to obtain the opening of museums, art galleries, libraries and gardens on Sundays, to promote the delivery of Sunday lectures on literary, philosophical, and scientific subjects, and to provide concerts of high-class music on Sundays. Like his great friend T.H. Huxley, Tyndall was committed to progressive scientific ideals ‘which challenged the hegemony of the traditional religious world view’ (ODNB), and in this lecture he argues that Sabbatarians should make common cause with the reformers, exhorting them to, ‘Back with your support the moderate and considerate demands of the Sunday Society, which scrupulously avoids interfering with the hours devoted by common consent to public worship. Offer the museum, the picture gallery, and the public garden as competitors to the public-house. By so doing you will fall in with the spirit of your time, and row with, instead of against, the resistless current along which man is borne to his destiny’ (pp. 44-45). Perhaps unexpectedly, Tyndall makes his case from a conservative standpoint: ‘Most of you here are Liberals; perhaps Radicals, perhaps even Republicans. In the proper sense of the term, I am a Conservative. Madness or folly can demolish: it requires wisdom to conserve [...] The first requisite of a true conservatism is foresight [...] We have here represented not a true, but a false and ignorant conservatism. The true conservative looks ahead and prepares for the inevitable. He forestalls revolution by securing, in due time, sufficient amplitude for the national vibrations’ (p. 45). The address was first published in the November 1880 issue of The Nineteenth Century and then separately published with small additions in this form, before being collected in Tyndall’s New Fragments (London, 1892).

Written by Robert Wallace (1831-1899), the theologian, sometime editor of The Scotsman, and radical Member of Parliament for Edinburgh East from 1886 to 1899, Irish Usurpation in British Politics is a closely-argued and witty attack on Gladstone’s proposal to omit sub-sections 3 and 4 of clause 9 of the Home Rule Bill, ‘the effect of which would be to leave Irish Members free to vote on all questions, British as well as Imperial, in Parliament’ (p. [3]) – essentially a precursor of Tam Dalyell’s ‘West Lothian Question’. Wallace – who had ‘with perfect heartiness defended this great principle of this Bill’, which ‘proposes to give [Home Rule] with a comparatively generous hand, although not with the fullness and absoluteness that I, for one, would have desired’ (loc. cit.) – objected to the amendments because they would ‘pervert the Bill, so that it shall be no longer simply a measure to give self-government to Ireland, but shall become at the same time a proposal to take away self-government from Great Britain’ (p. 4). Wallace concludes by restating his opposition to the amendments and characterising it as that of a faithful friend: ‘I have observed that Governments, like individuals, have two classes of friends, the candid and the sugar-candied [...] For myself, I am afraid there can be little doubt about the category to which I belong, for, unfortunately, Nature has not endowed me with any plethora of saccharine attributes [...] to begin with, and such as may have been bestowed, have, I apprehend, become almost atrophied by negligent culture’ (p. 16). Gladstone’s second Government of Ireland Bill passed the House of Commons on 1 September 1893 after eighty-two sittings and an extended session, and ‘Gladstone personally took the bill through the committee stage in a remarkable feat of physical and mental endurance’ (ODNB); as Roy Jenkins wrote, ‘In different parts of the House, even among his bitterest opponents, there was a sense of witnessing a magnificent last performance by a unique creature, the like of whom would never be seen again’ (Gladstone (London: 1995), p. 603). Nonetheless, the bill was defeated by Salisbury’s Tory majority in the House of Lords, and the ‘Grand Old Man’ resigned office on 3 March 1894, to be replaced by Rosebery. This pamphlet is very rare: we can trace only one copy in UK institutional collections (LSE), and WorldCat identifies one further copy, at Boston Public Library.

Lecky’s Democracy and Liberty, ‘a long discursive treatise on contemporary politics’ (ODNB), was first published in 1896, and considered the effect of democracy on social and individual freedom: it ‘usefully explore[d] such issues as the tyranny of the majority and the possibility of the democratic despot, and it included interesting reflections on proportional representation and referendums as means by which to limit the dangers of democracy. It also encompassed an early acknowledgement of the potential incompatibility of democracy and capitalism’ (loc. cit.). The ‘Cabinet Edition’ was published in two volumes in 1899, with a new and substantial introduction by Lecky, and, ‘In consequence of very many requests from purchasers of the earlier editions of “Democracy and Liberty”, I have determined to print separately, and uniformly with those editions, some copies of the Introduction to the revised Cabinet Edition’ (p. [v]). The new introduction is particularly interesting, because the first edition was written in the immediate aftermath of the 1892-1895 Liberal administration of Gladstone and Rosebery, which was replaced by Salisbury’s Conservatives, and Lecky compares the political history of the following years with his predictions in the first edition: ‘Few persons who had watched English politics since Mr. Gladstone dislocated the Liberal party on the question of Home Rule doubted that the Election of 1895 would involve the Home Rule party in disaster, but very few persons accurately measured the extent and the duration of the disaster. It was not simply that a Unionist Government came into power with a larger majority than that of any other Government since 1832. The Opposition which confronted it was so divided, disintegrated and discredited that it was in reality far weaker than might appear from its nominal numerical strength. In the three sessions that have elapsed since the election, the dominant power has committed several mistakes and sometimes shown much weakness, but, in spite of many predictions, the unity of the party remains unbroken and unforced, while its opponents have hitherto totally failed to attain any real or even apparent consolidation. There has been, indeed, scarcely any organised opposition, and the whole working of party government has been enfeebled by the fact’ (p. xi).