PRESENTED BY THE TRANSLATOR

VIRGIL Maro, Publius, and Giovanni Andrea dell’ANGUILLARA (trans.).

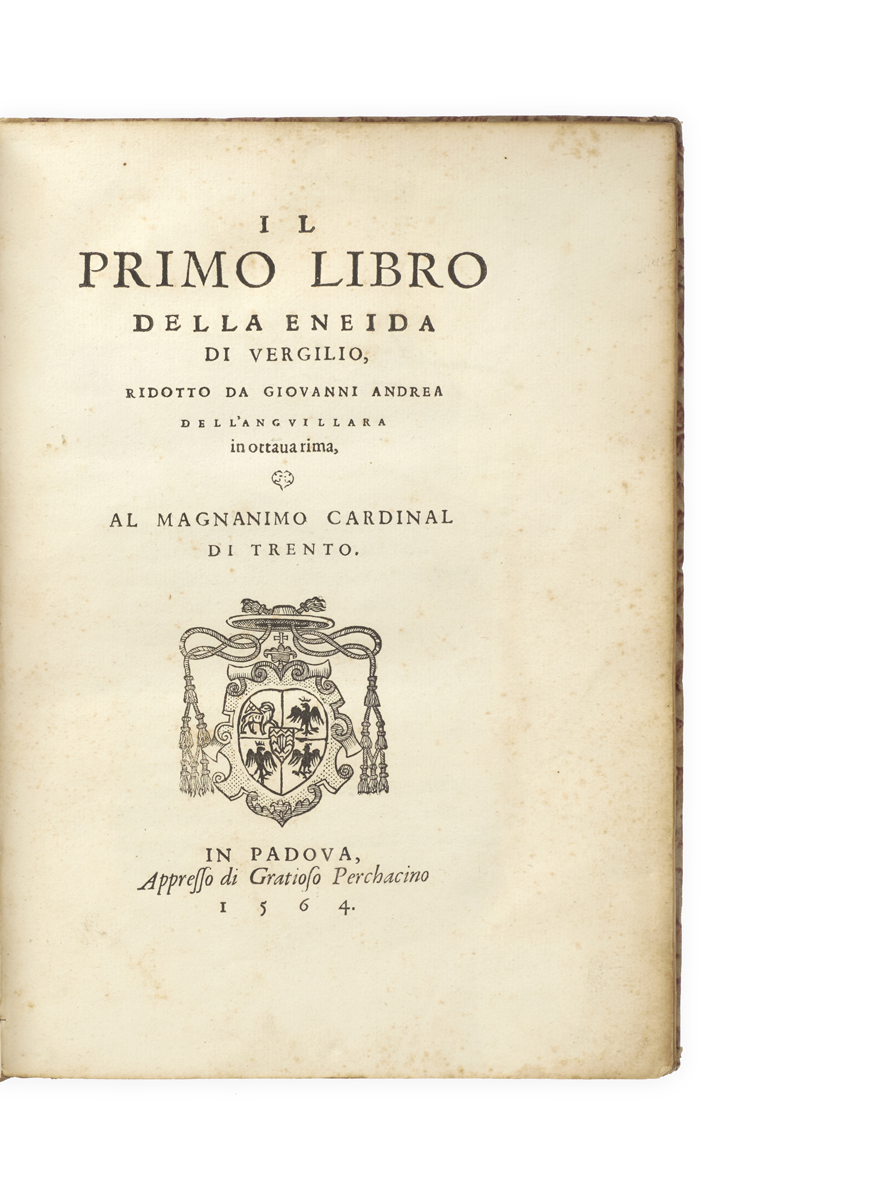

Il primo libro della Eneida di Vergilio, ridotto da Giovanni Andrea dell'Anguillara in ottava rima …

Padua, Gratioso Perchacino, 1564.

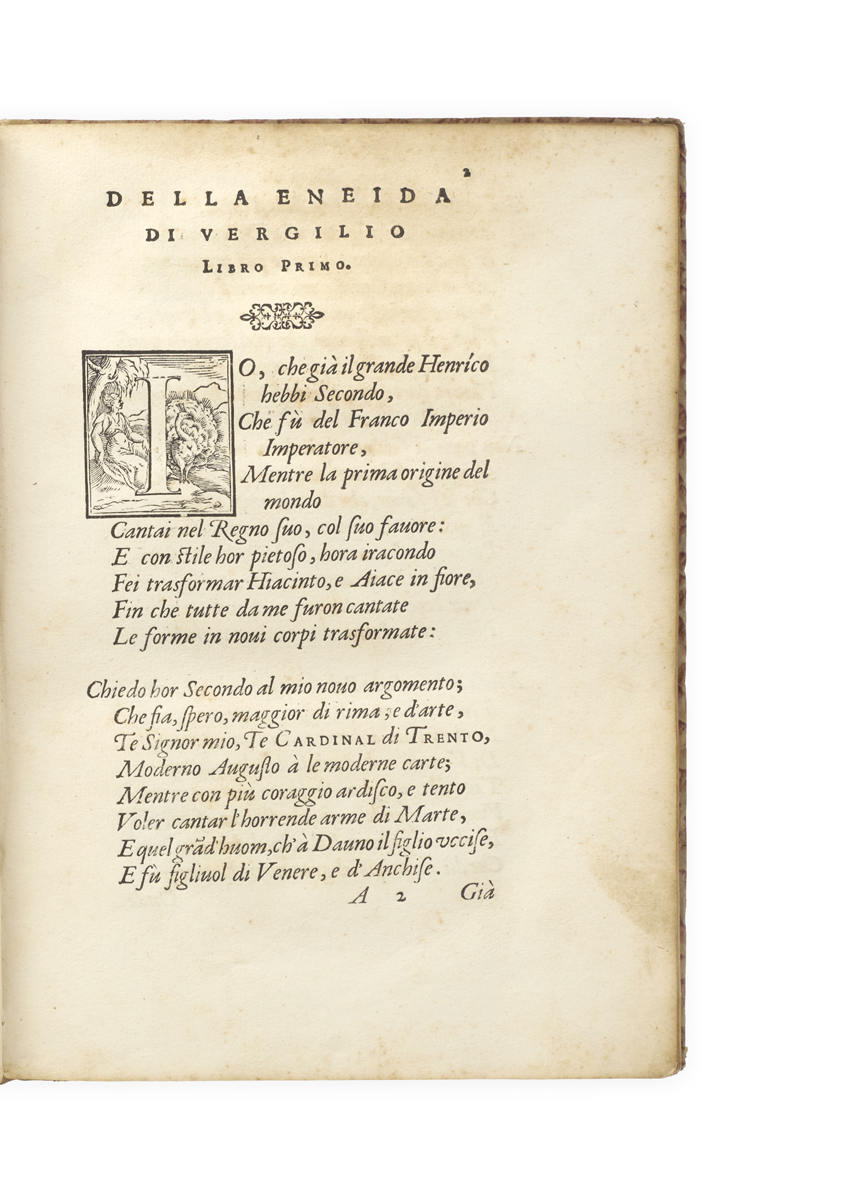

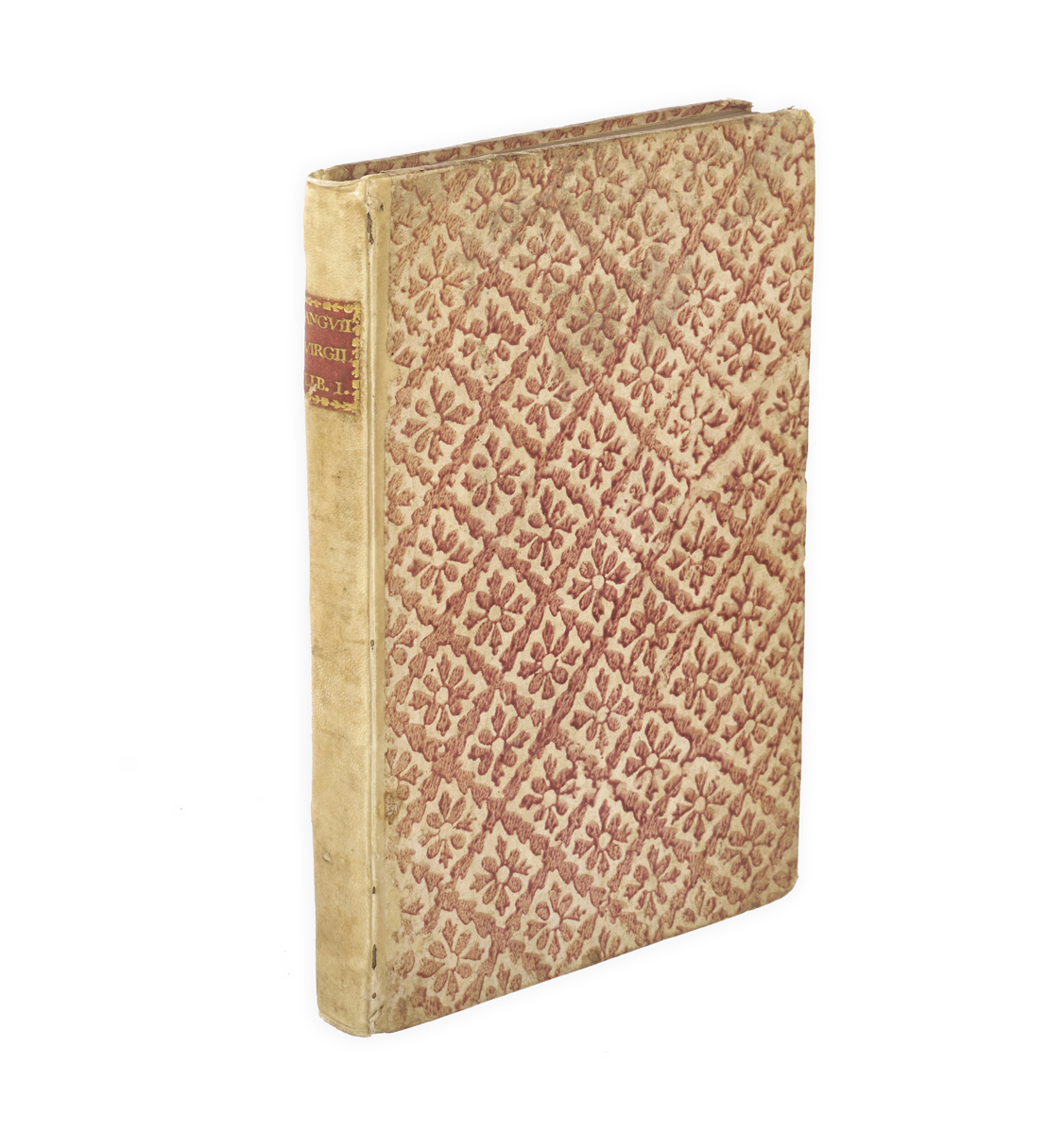

4to, ff. 47, [1]; printed in italic type, woodcut arms of dedicatee (Cristoforo Madruzzo Cardinal of Trento) to title, large woodcut historiated initial to f. 2; light foxing to early leaves, a few spots elsewhere, but a very good copy; in eighteenth-century Italian vellum-backed boards with patterned paper sides, gilt red morocco lettering-piece to spine; author’s ink inscription to title verso ‘Giovanni Andrea dell’Anguillara dono di propria mano’.

Added to your basket:

Il primo libro della Eneida di Vergilio, ridotto da Giovanni Andrea dell'Anguillara in ottava rima …

First edition of the first book of Anguillara’s verse translation of the Aeneid, a copy printed on strong paper and inscribed by the author. The humanist, poet, and successful translator of Ovid Giovanni Andrea dell’Anguillara (1517–1572) undertook to translate into Italian ottava rima the first four books of Virgil’s Aeneid, but only printed two. According to Argelati, Anguillara left his Aeneid unfinished on purpose in order not to stand in competition with his friend, the translator Annibal Caro; ‘Had he finished it, it would have been more pleasing to read than any of the above named [Caro and Domenichi as well as others] if we can judge by this specimen’ (G. Baretti, The Italian Library (London, 1757), p. 132).

A number of copies are known to have been printed on strong paper and to bear the same authorial inscription – further evidence of this being intended as a special, non-trade issue is to be found in the last leaf, which bears the somewhat threatening printed valediction ‘All those who thank the author for this gift, with words or letters, will be met by Aeneas in the Elysian Fields and praised by Anchises; the others might find themselves in Hell, and not without guilt. Let replies be addressed to Venice, to the Siren Bookshop’ (trans.).

EDIT16 33755; F. Argelati, Biblioteca dei volgarizzatori IV, p. 149; Haym, Biblioteca italiana II, 206; Schweiger II, 1232.