AN EARLY STEAM-ENGINE

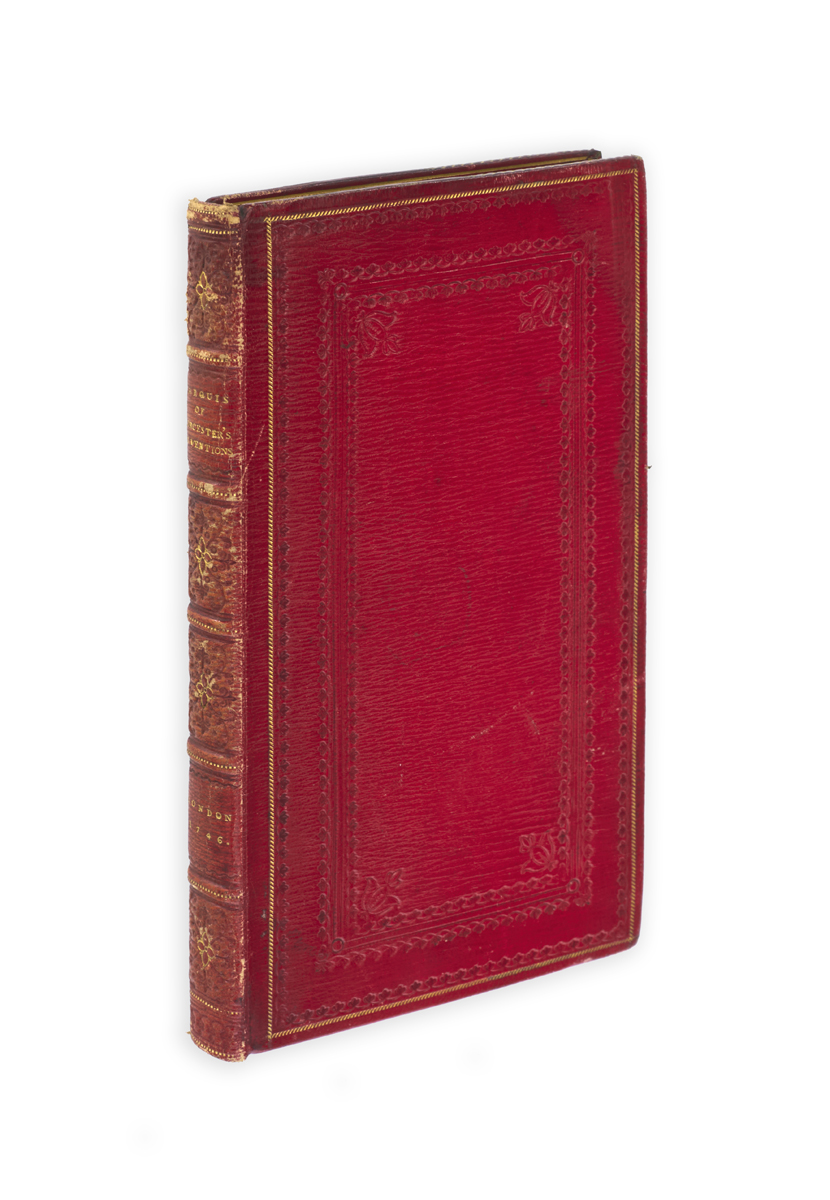

WORCESTER, Edward Somerset, Marquess of.

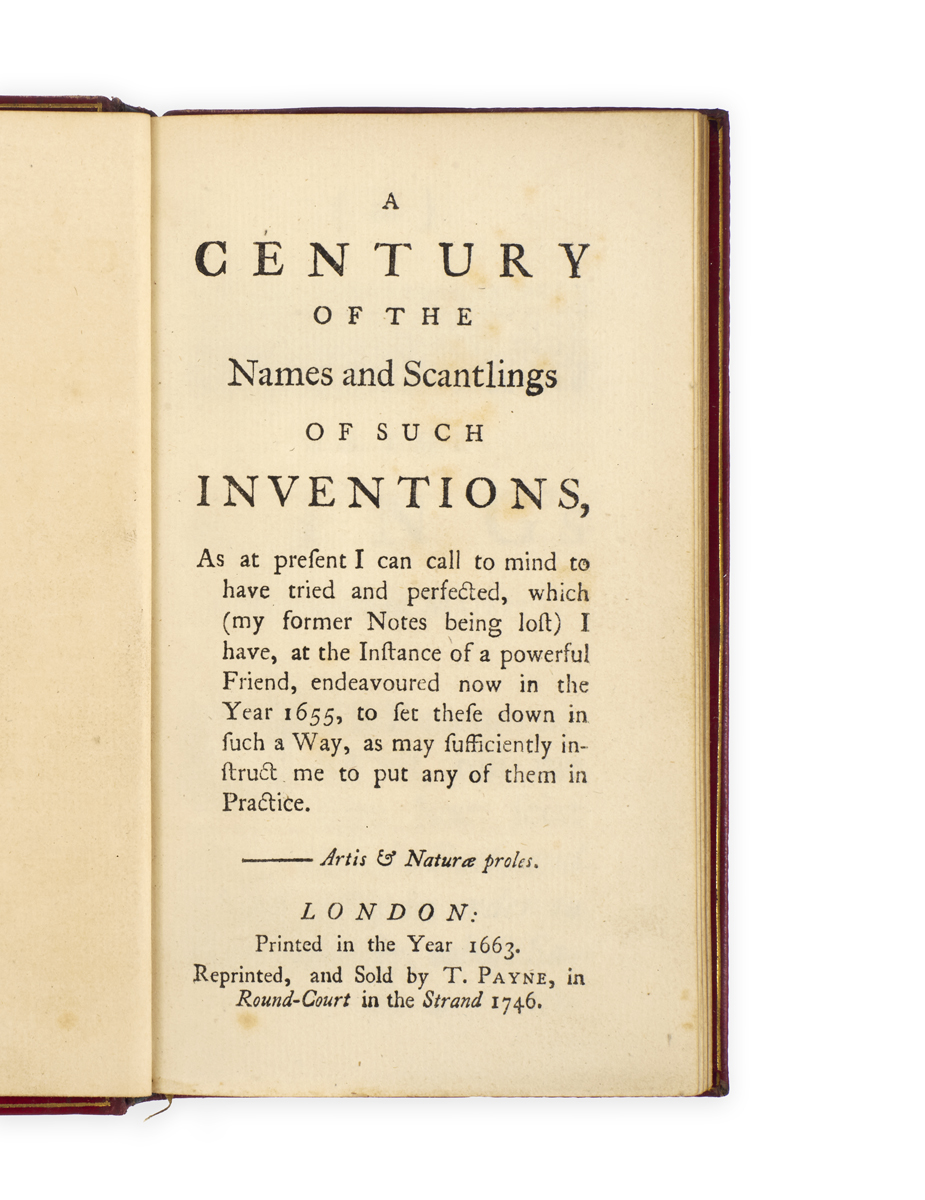

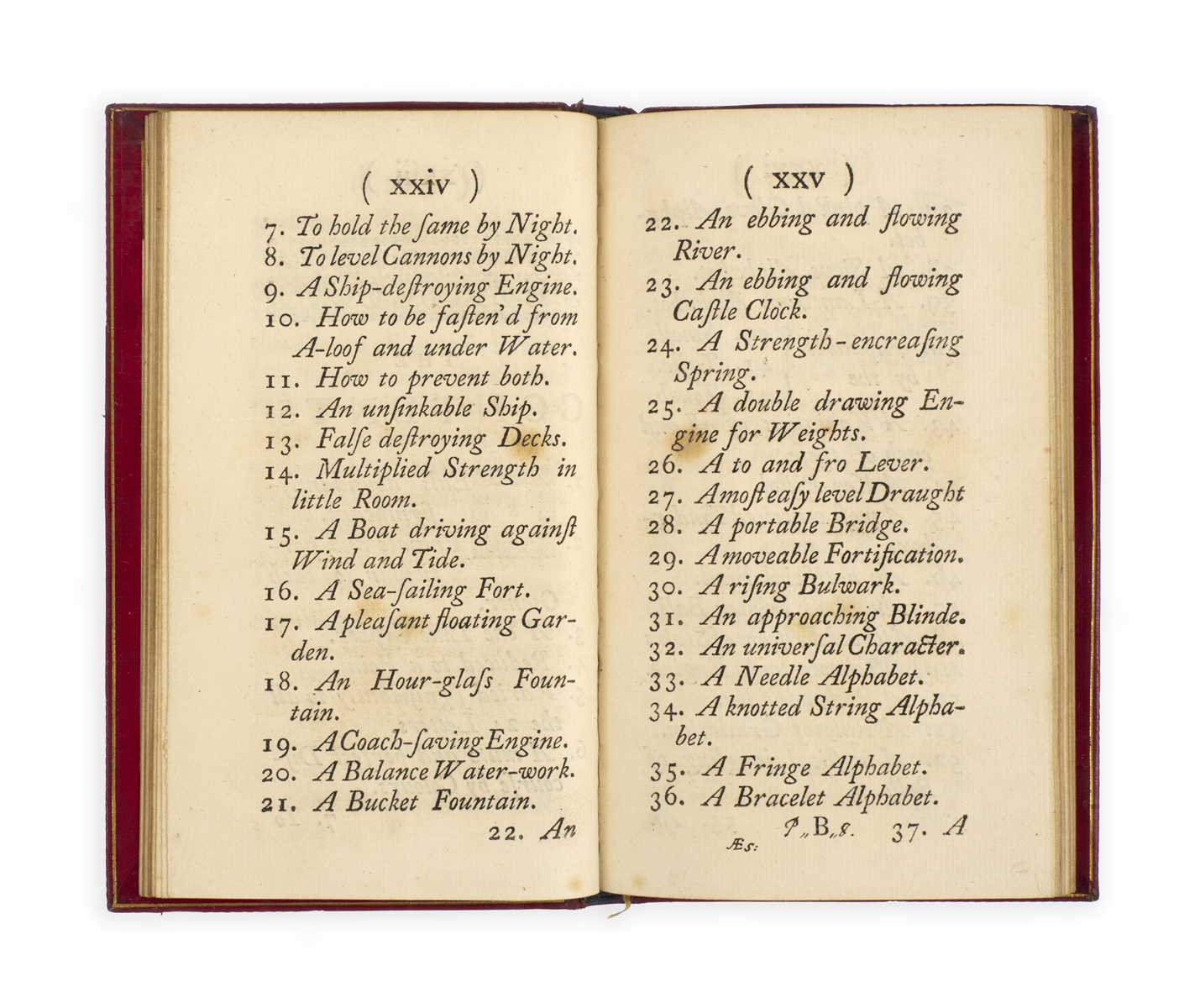

A Century of the Names and Scantlings of such Inventions, as at present I can call to Mind to have tried and perfected, which (my former Notes being lost) I have, at the Instance of a powerful Friend, endeavoured now in the Year 1655, to set these down in such a Way, as may sufficiently instruct me to put any of them in Practice … London: Printed in the Year 1663.

Reprinted, and sold by T. Payne … 1746.

12mo, pp. xxx, 94, [2, advertisements]; a fine copy in early nineteenth-century red straight-grain morocco by Charles Hering, with his ticket, covers panelled in gilt and blind, spine tooled in compartments, part-morocco pastedowns; mark of ownership on B1 of Philip Bliss, for whom the work was probably bound; bookplate of Charles Barclay (1780–1855); a pencil note suggests this was bought at the ‘D. of Marlborough’s sale

Added to your basket:

A Century of the Names and Scantlings of such Inventions, as at present I can call to Mind to have tried and perfected, which (my former Notes being lost) I have, at the Instance of a powerful Friend, endeavoured now in the Year 1655, to set these down in such a Way, as may sufficiently instruct me to put any of them in Practice … London: Printed in the Year 1663.

Second edition of a charming catalogue of inventions claimed to have been ‘tried and perfected’ by the royalist second Marquess of Worcester (1601–1667), first published in 1663.

Banished in 1649 and then imprisoned in 1653, on his release Worcester set up an establishment at Vauxhall to work on his inventions, employing the Dutch(?) engineer (and former gunsmith to Charles I) Kaspar Kalthoff, who had been at work on steam engines since at least the 1630s.

The most significant of these was no. 68, an ‘admirable and most forcible way to drive up Water by Fire’, a sort of prototype steam-engine, which was seen and admired by Cosimo de’ Medici and Samuel Sorbière, but dismissed by Hooke as a perpetual motion fantasy. Worcester, subject of much myth-making since, was supposedly buried with it, but a gruesome Victorian exhumation revealed no such machine.

Also suggested, but with insufficient detail, are a machine ‘to make a man fly; which I have tried with a little Boy of ten years old in a Barn’; a calculator; various automata; a floating garden on the Thames; universal languages employing silk knots, gloves, bracelets, the holes in a sieve, and, the mind boggles, smell; and what sounds like a limpet mine.

The antiquary and book collector Philip Bliss (1787–1857) became an assistant at the Bodleian in 1808; he ‘assembled a substantial library, much of it related to his biographical and bibliographical researches and thus strong in books with Oxford connections, sixteenth- and seventeenth-century English poets, and works by ‘royal and noble authors’ … His books bear the discreet ownership mark of a ‘P’ written before the printed signature ‘B’, with a two-digit year of purchase following’ (Oxford DNB). Bliss bought this copy in 1808; some of the books of the fifth Duke of Marlborough, removed from Blenheim, were sold in Oxford in 1840, and Bliss was a buyer at the sale, though this must have passed in the opposite direction, and thence to Barclay.