BURLAMAQUI, Jean Jacques.

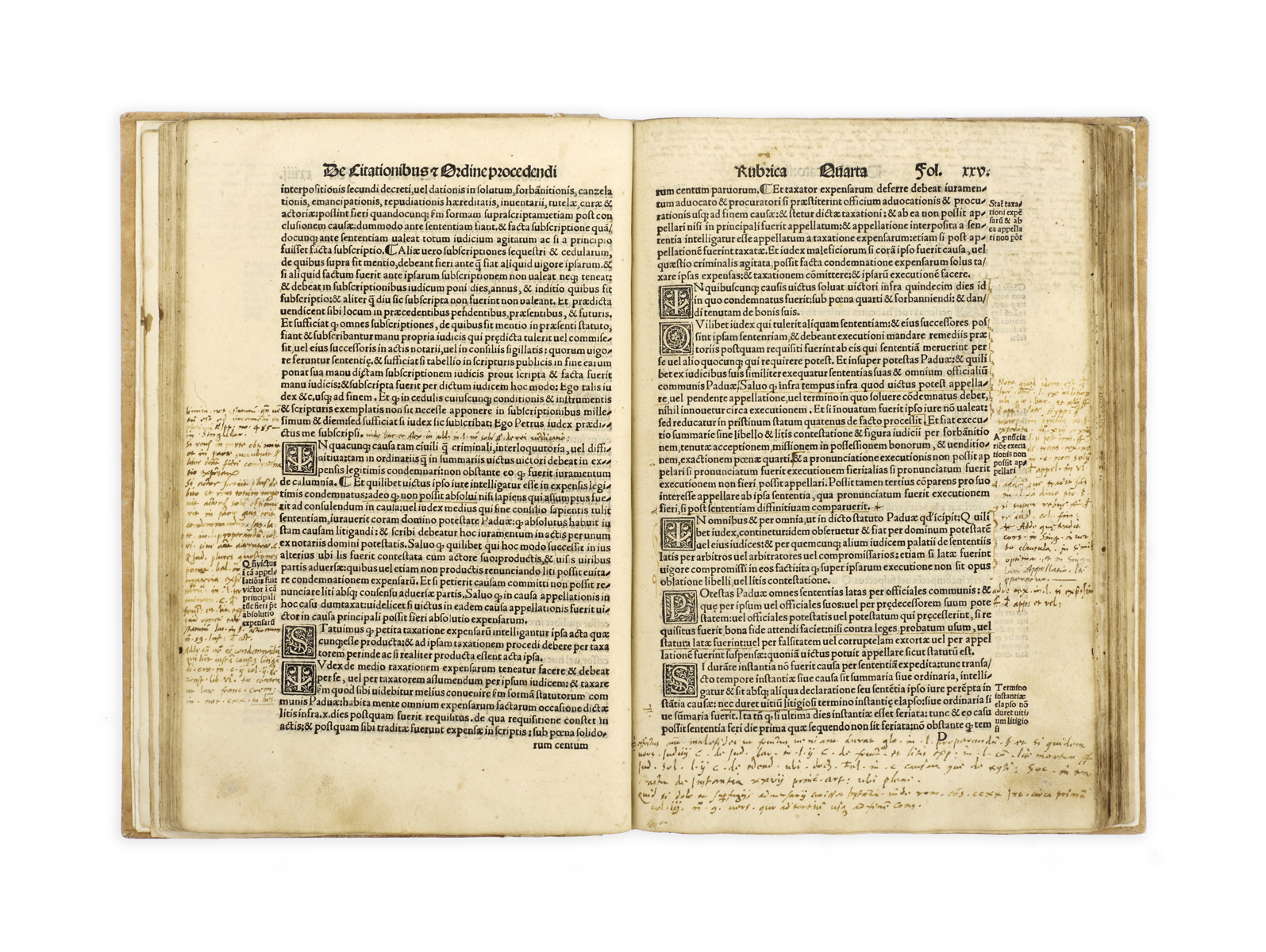

Principes du droit naturel.

Geneva, Barrillot & fils, 1747.

[bound with:]

BURLAMAQUI, Jean Jacques. Principes du droit politique. [Geneva, C. & A. Philibert], 1754.

4to, pp. xxiv, 352; vi, 305, [1 blank; occasional browning and foxing, a small worm-hole through the gutter in one quire skilfully filled in; good copies in contemporary stiff vellum, flat spine with gilt lettering-piece.

First edition of the first work, bound with a very early edition of the second work. The Droit politique was first published posthumously in 1751 as the necessary companion to the Droit naturel; when in contemporary bindings, they are sometimes found together in various combinations of editions.

Burlamaqui, the eminent editor of Grotius and Pufendorf, was professor of law at Geneva and a member of the city’s council of state. His writings on natural law circulated widely in America in the decades leading up to the Revolution, with Jefferson foremost among his readers. ‘Burlamaqui reveals more explicitly than any other writer read by Jefferson the logical substructure upon which Jefferson built when he wrote in the Rough Draft [of the Declaration of Independence]: “We hold these truths to be sacred and undeniable; that all men are created equal & independent, that from that equal creation they derive rights inherent & inalienable, among which are the preservation of life, & liberty & the pursuit of happiness; that to secure these ends, governments are instituted among men” ’ (White, Philosophy of the American Revolution, p. 163). For the dissemination of Burlamaqui’s works in America, see Harvey, Jean Jacques Burlamaqui, pp. 79–105.

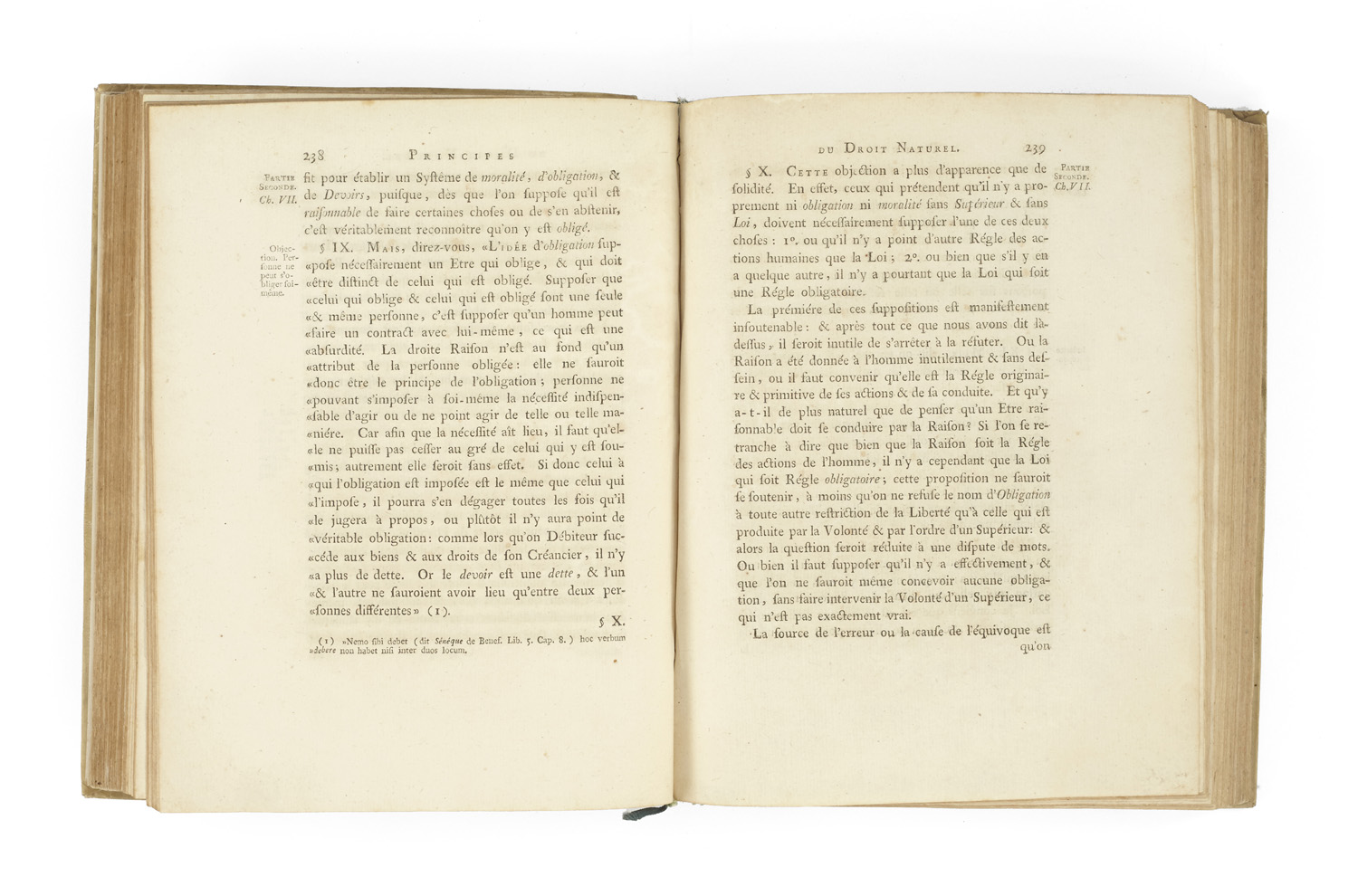

In the debates leading up to the Declaration of Independence, Burlamaqui’s ideas powerfully swayed Jefferson and the jurist James Wilson not to identify property as a natural right. This was an important and awkward political issue, because while nobody claimed that the American Indians, though primitive, had no natural rights, the admission of a natural right to property would put under suspicion virtually all land held by descendants of European settlers in America (also contentious was the matter of a natural right to property in relation to the legitimacy of slavery). Jefferson and Wilson, both of whom owned his works in the original French, found in Burlamaqui a very clear message about property and rights, for within the natural state of man Burlamaqui made a distinction between the primitive, original state as created by God, and adventious states where man is placed by his own acts: the ‘property of goods’ is one such adventious state. In regard to rights, Burlamaqui lay down a parallel distinction between natural rights appertaining originally and essentially to man, and acquired rights, being those which man does not naturally enjoy but are owing to his own procurement: the right to self-preservation might be cited as an example of a natural right, the right to property as an example of an acquired right. If Jefferson and his colleagues realised that the designation of property as an unalienable human right would be politically unwise, it was Burlamaqui who showed that it was philosophically unjustified (see Garnsey, Thinking about property, pp. 222–5).

En français dans le texte 150; Lonchamp 499.