CONFUCIANISM BETWEEN MONOTHEISM AND ATHEISM

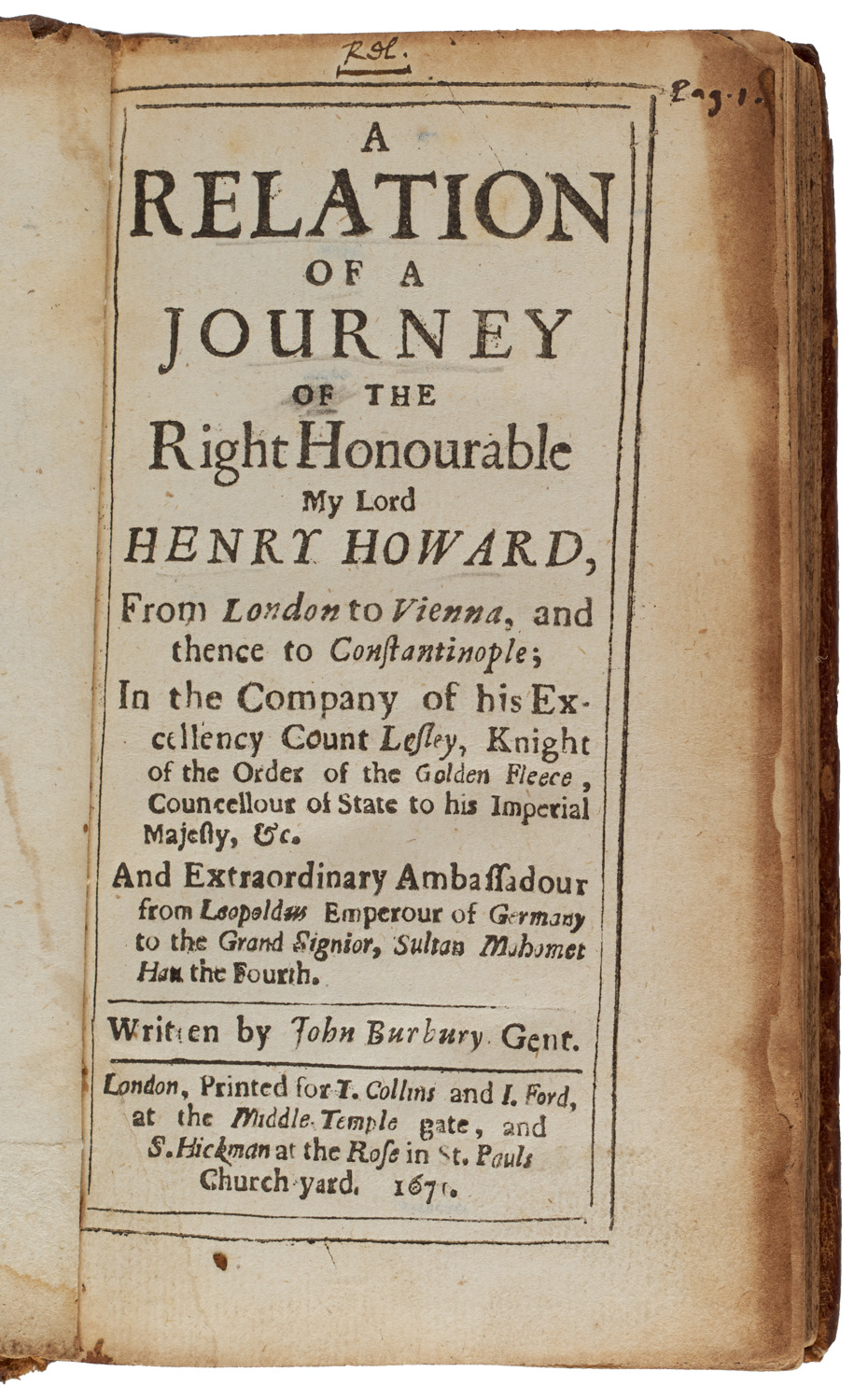

NAVARRETE, Domingo Fernández.

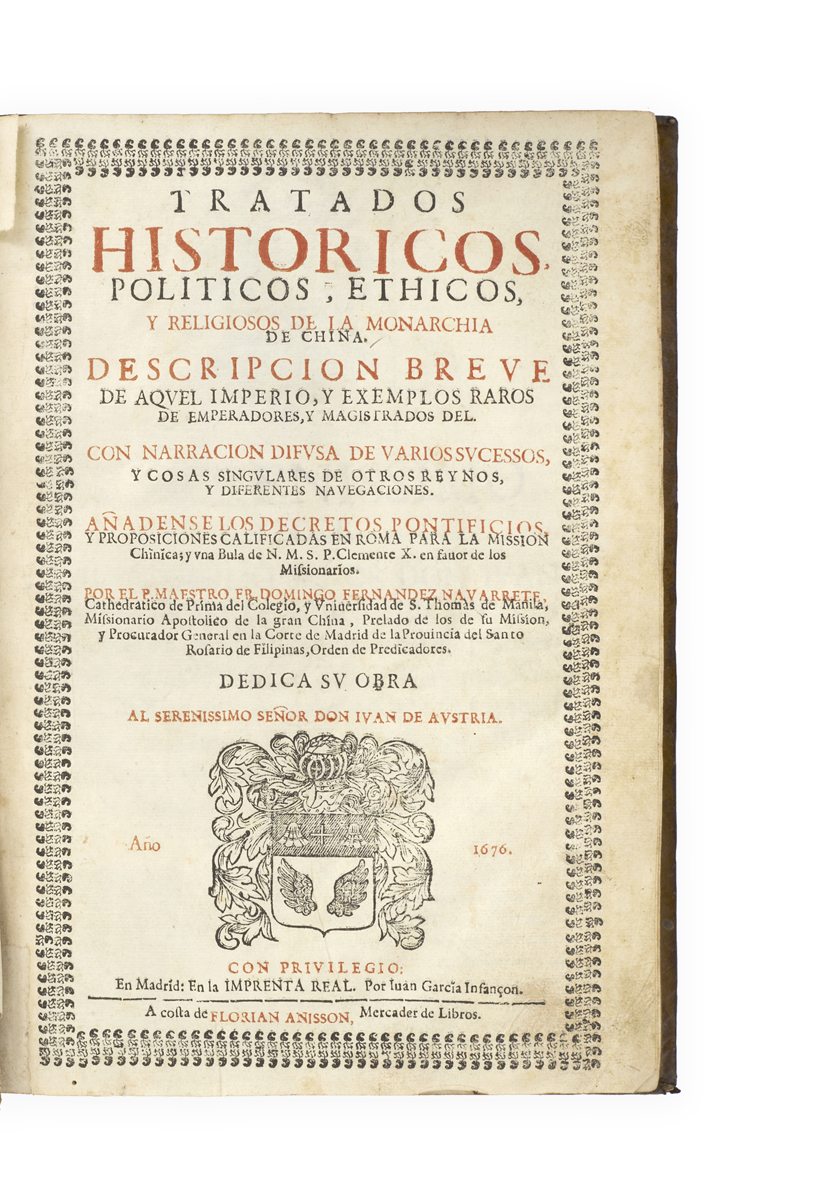

Tratados historicos, politicos, ethicos, y religiosos de la monarchia de China. Descripcion breve de aquel imperio, y exemplos raros de emperadores, y magistrados del. Con narracion difusa de varios sucessos, y cosas singulares de otros reynos, y diferentes navegaciones. Añadense los decretos Pontificios, y proposiciones calificadas en Roma para la mission Chinica; y una Bula de N.M.S.P. Clemente X en favor de los Missionarios …

Madrid, Juan Garcia Infançon for Florian Anisson, 1676.

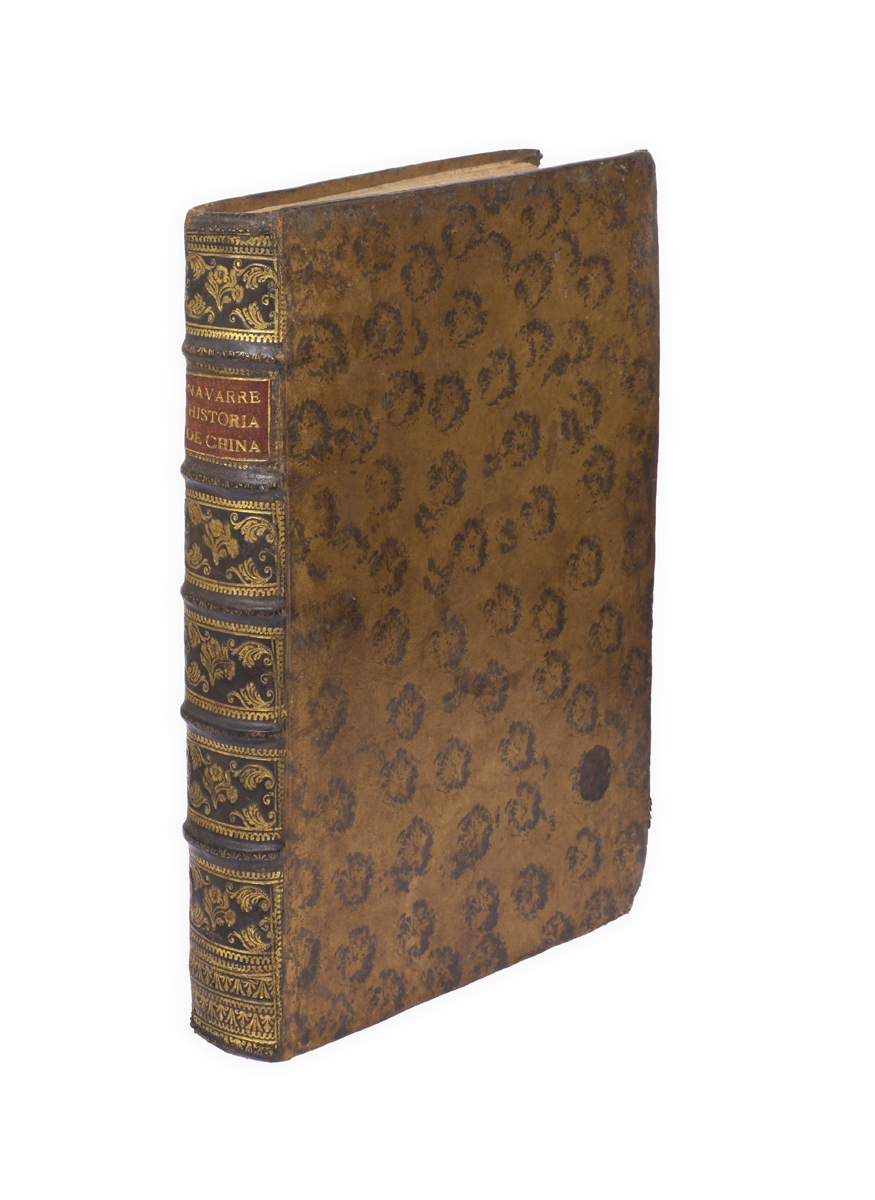

Folio, pp. [20], 518, [26, index]; title in red and black within border, woodcut arms to title, engraved arms at head of p. [3], woodcut initials and tailpieces, text in two columns; a little damp staining and toning, small paper flaw to top right corner of p. 357, very small amount of worming to top corners from p. 467; overall very good in contemporary mottled brown calf, spine gilt in compartments with red morocco lettering-piece, red edges; a few small wormholes at foot of spine, corners bumped, some small marks and abrasions to covers.

Added to your basket:

Tratados historicos, politicos, ethicos, y religiosos de la monarchia de China. Descripcion breve de aquel imperio, y exemplos raros de emperadores, y magistrados del. Con narracion difusa de varios sucessos, y cosas singulares de otros reynos, y diferentes navegaciones. Añadense los decretos Pontificios, y proposiciones calificadas en Roma para la mission Chinica; y una Bula de N.M.S.P. Clemente X en favor de los Missionarios …

Scarce first edition, one of the most important early studies of Chinese history, religion, philosophy, and culture, by the Spanish Dominican Domingo Navarrete (d. 1689).

Born in 1618, Navarrete entered the Dominican Order in 1635 and joined the missions, initially to the Philippines, in 1646. He first arrived in Macao, partly by accident, in 1658, and spent the next eleven years in mainland China before returning to Europe via India and the Cape in 1672. This, his major work on China, was published while Navarrete was residing at the Priory of Passion in Madrid, shortly before his promotion to Archbishop of Santo Domingo in what is now the Dominican Republic. It consists of a history of China and a lengthy discussion of Chinese philosophy, in particular the Confucianism of the Chinese literati, as well as an account of Navarrete’s travels, beginning with his journey to the Philippines via Mexico and ending with his return trip to Rome from China more than two decades later.

By all accounts, Navarrete fell in love with China and was a great admirer of Chinese history and culture. Nevertheless, he quickly became famous and even notorious for his denunciation of the evangelizing practices and interpretation of Chinese philosophy then being expounded by Jesuit missionaries. Since the time of Matteo Ricci (1552–1610), Jesuits in China had argued that Chinese Confucianism retained elements of primitive monotheism – and even Christianity – while supposing that the rites practiced by Chinese Confucians were not religious but merely civil and political, and therefore permissible. In opposition, Navarrete argued that the Chinese rites were religious and therefore idolatrous, and that Chinese Confucianism was materialist and atheist, and he openly condemned the Jesuits for allowing such practices to continue. In Europe, where a number of vested interests – including Blaise Pascal and the Jansenists – sought to strike at Jesuit casuistry and influence, his work, one of the few major non-Jesuit works of Sinology of the period, proved popular, and it remained an important source for the papal congregation which eventually banned the practicing of the Chinese rites outright in 1704, thereby bringing to an end almost a century of Jesuit missionizing in China.

Alongside Navarrete’s own text, the work also includes both the first publication of a treatise written against Matteo Ricci and his evangelizing practices by Ricci’s Jesuit successor Niccolò Longobardo (1559–1654) – a document of great importance for later anti-Jesuit polemicists who appropriated Longobardo’s criticisms for their cause – and a number of earlier judgements by the Holy Office against the Chinese Rites. An English translation of Navarrete first appeared in 1704: it was on the basis of this translation that John Locke came to cite Navarrete in the fifth edition of his An Essay concerning Human Understanding (1706) in order to argue that the Chinese – and therefore mankind in general – had no innate idea of God.

Cordier, pp. 31–35; Hill 582; Lust 21. See J.S. Cummins, A Question of rites: Friar Domingo Navarrete and the Jesuits in China (Aldershot and Brookfield VT, 1993).