'THE BESTSELLER OF THE GERMAN ENLIGHTENMENT'

NICOLAI, [Christoph] Friedrich.

The Life and Opinions of Sebaldus Nothanker. Translated from the German … by Thomas Dutton, A. M. …

London: Printed by C. Lowndes, and sold by H.D. Symonds, 1798.

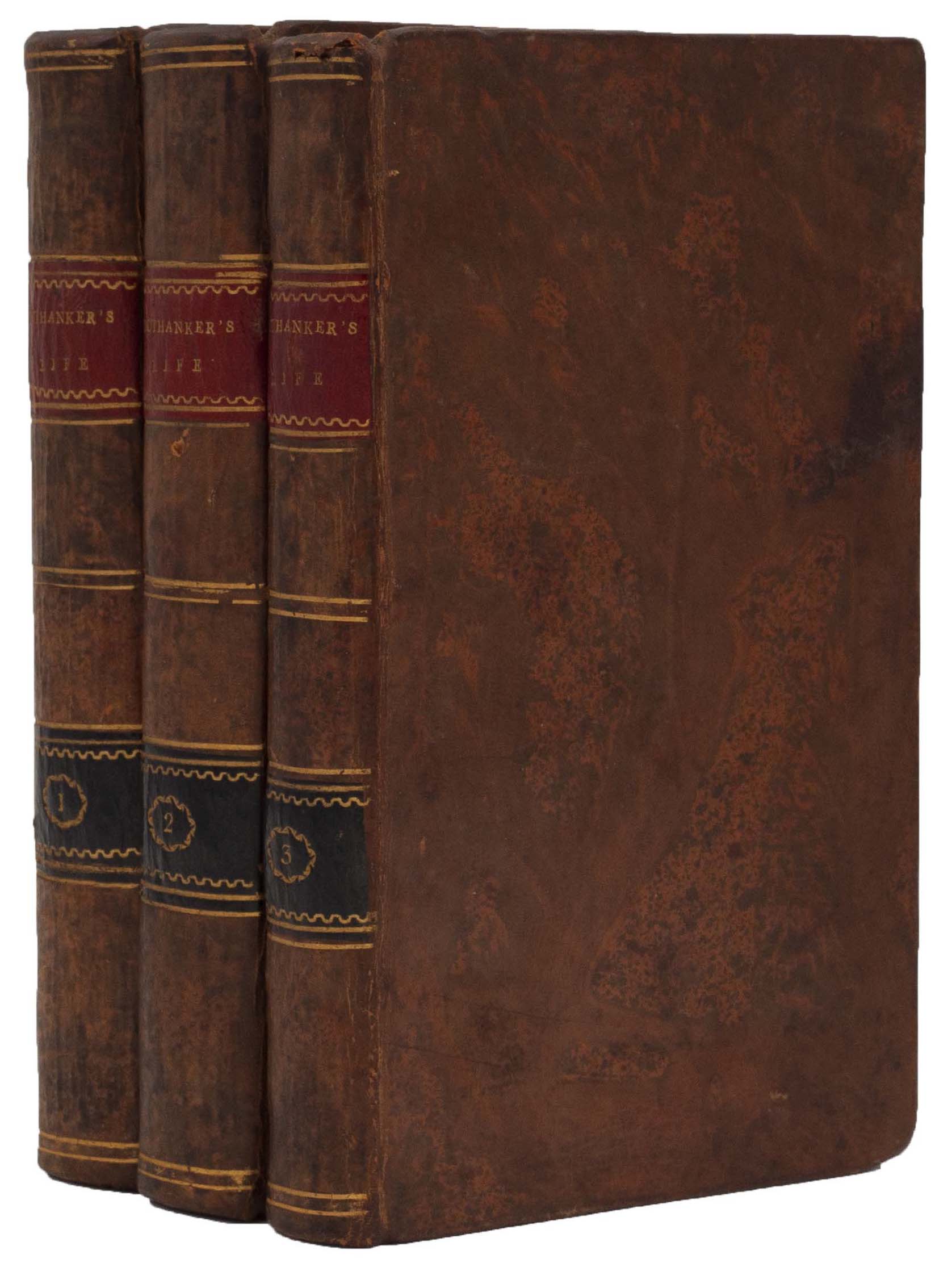

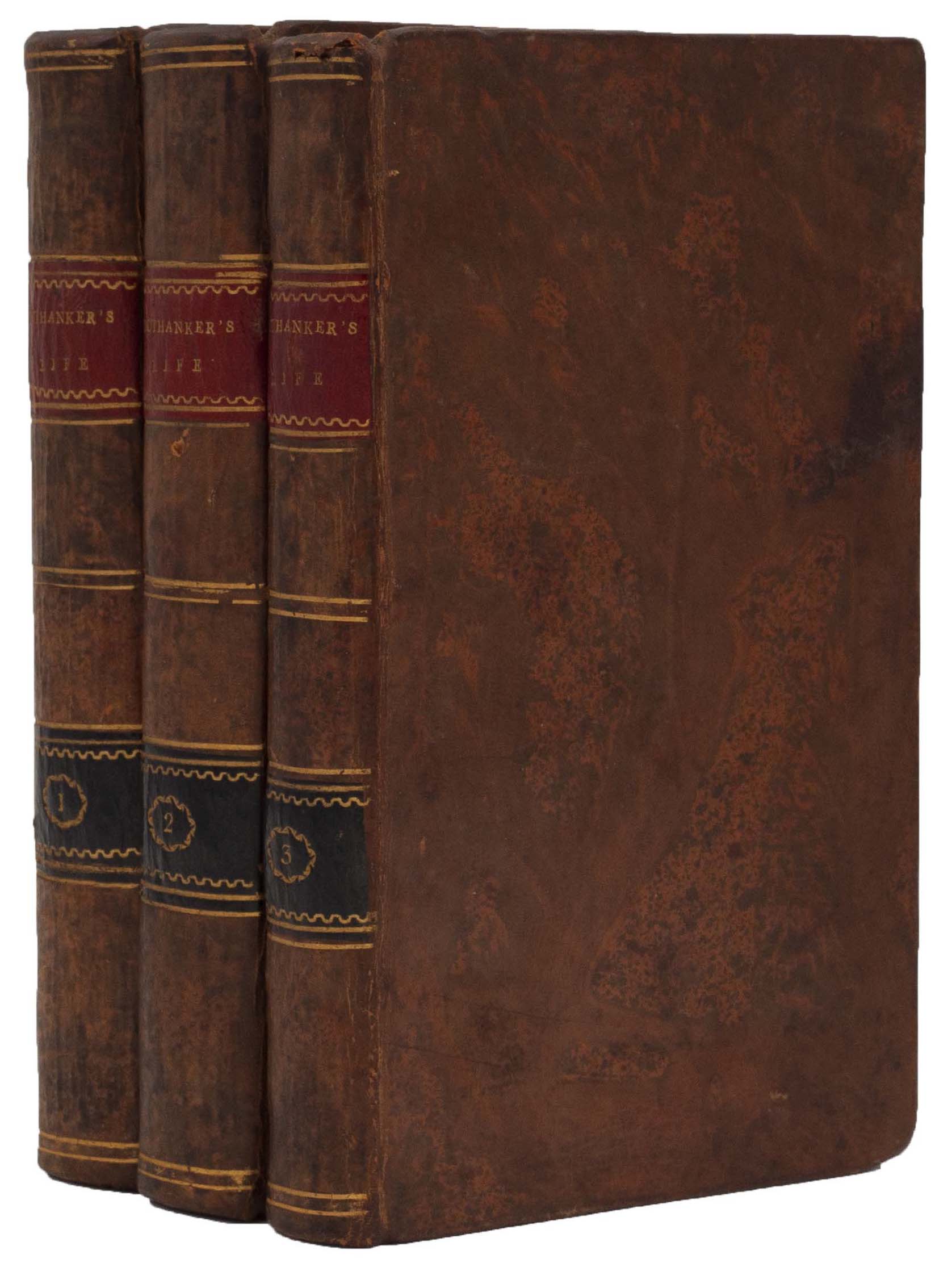

Three vols, 12mo, pp. [2], xxvi, 356; [2], 395, [1]; 289, [1]; with an etched illustration (bound as a frontispiece) to volume II by Daniel Chodowiecki (the costumes of eight Berlin preachers described on pp. 147–154; printed from the same plate as the German original with a new page reference), not mentioned in ESTC but clearly required; a few spots and stains, the final blank verso in volume II pasted onto the free endpaper, but a very good copy, in contemporary tree calf, red and black morocco spine labels; early ownership inscriptions to title-pages ‘William Tew from Paul Twigg’.

Added to your basket:

The Life and Opinions of Sebaldus Nothanker. Translated from the German … by Thomas Dutton, A. M. …

First edition in English, very scarce, of Nicolai’s Das Leben und die Meinungen des Herrn Magister Sebaldus Nothanker (1773–6), ‘probably the literary bestseller of the German Enlightenment’ (Selwyn), translated into many languages and much re-printed. It is sometimes considered the first ‘realistic’ German novel, but is at its heart a scathing satire on, among other things, religion and the book trade. Immensely engaging, this English translation was very well received in the Monthly Review.

The idealistic parson Sebaldus Nothanker, deprived of his congregation by Lutheran zealots, is saved from potential destitution by his friend the bookseller Jeronymo (originally Heironymus), often considered to be a self-portrait of Nicolai. Jeronymo finds Nothanker a position as a proofreader in Leipzig, where dialogues between him and a disillusioned hack ‘Doctor’ satirise the sausage-factory production of trivial contemporary literature. The Doctor explains how booksellers commission works by the yard on particular subjects, which they then use to barter for better works at book fairs; how they aim for the most text for the smallest price from their authors; and how hawkers trade the newest literature from France and England to ‘Translating Manufactories’. There are ‘fashionable translators, who accompany their translation with a preface, in which they assure the public, that the original is excellent; – learned translators, who improve upon their work, accompany it with remarks, and assure us that the original is very bad but that they have made it tolerable; – translators, who translate themselves into originals … leave out the beginning and end and improve the remainder at pleasure … and publish the books as their own production’. Nothanker is astonished, but his friend Jeronymo is pragmatic, realising the difficult economics of the trade, and complaining that German authors, unlike the French and English, do not know how to write for a wide audience. Nicolai’s preface explains that normally novels work up to a happy resolution with a marriage, but he favours veracity. At the end, the characters are rewarded not for good deeds but by blind luck, after winning a lottery.

The Anglophile writer and bookseller Nicolai (1733–1811), himself son of bookseller, was a friend of Lessing and Moses Mendelssohn with whom he edited several literary periodicals. Best known for the present work and his satire on Goethe, Freuden des jungen Werthers (1775), he also published (and possibly translated) works from English.

ESTC shows eight complete copies only: BL, Cambridge, Trinity Cambridge; Harvard, Johns Hopkins, Library Company of Philadelphia, Library of Congress, and UC Davis.

Garside, Raven, and Schöwerling 1798: 50; Pamela Eve Selwyn, Everyday Life in the German Book-Trade: Friedrich Nicolai as Bookseller and Publisher in the Age of Enlightenment (2000).