‘TIME & COUNSELL MAY REFORME MANY THINGS:

INDUSTRIE & IMITATION MUST REFORME THE REST’

COPE, Walter, Sir.

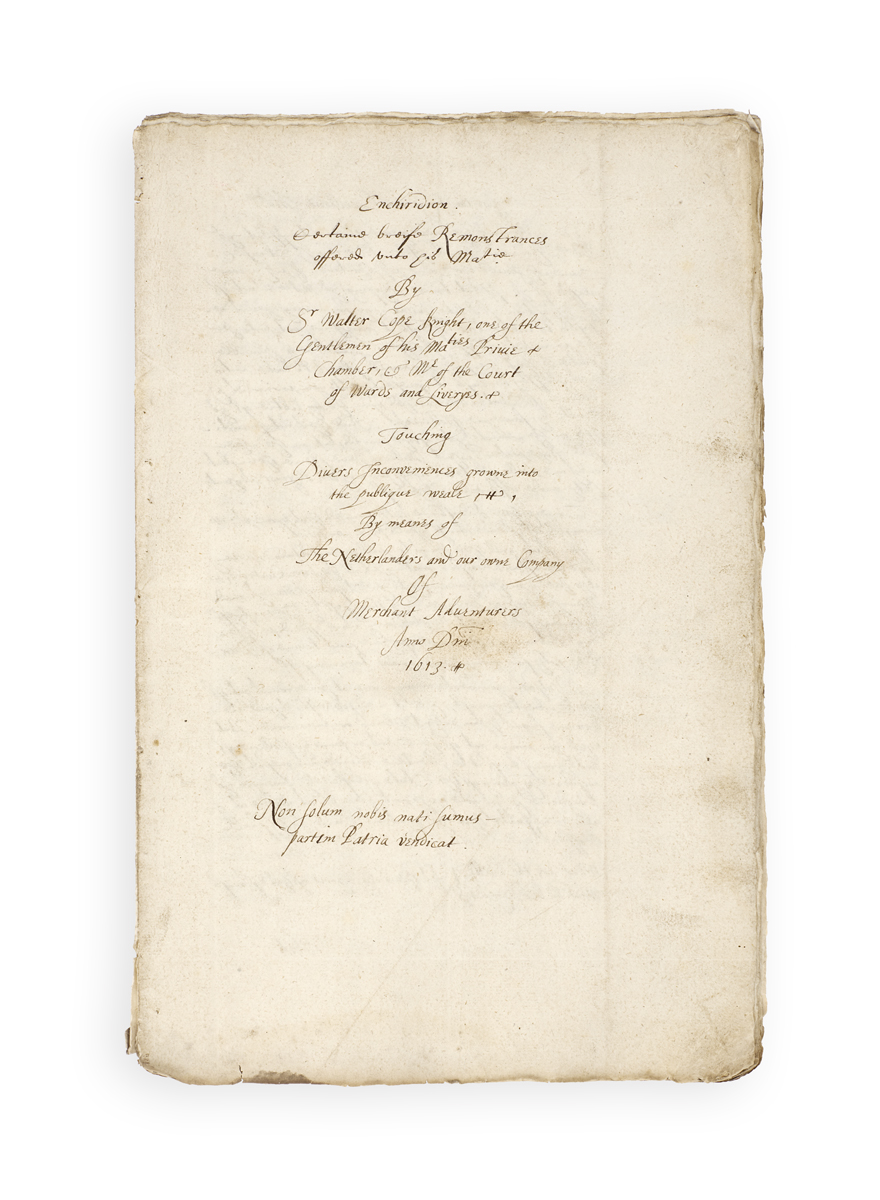

‘Enchiridion. Certaine breife Remonstrances offered unto his Ma[jes]tie … Touching divers Inconveniences growne into the publique Weale by meanes of The Netherlanders and our owne Company of Merchant Venturers’.

[London?], 1613.

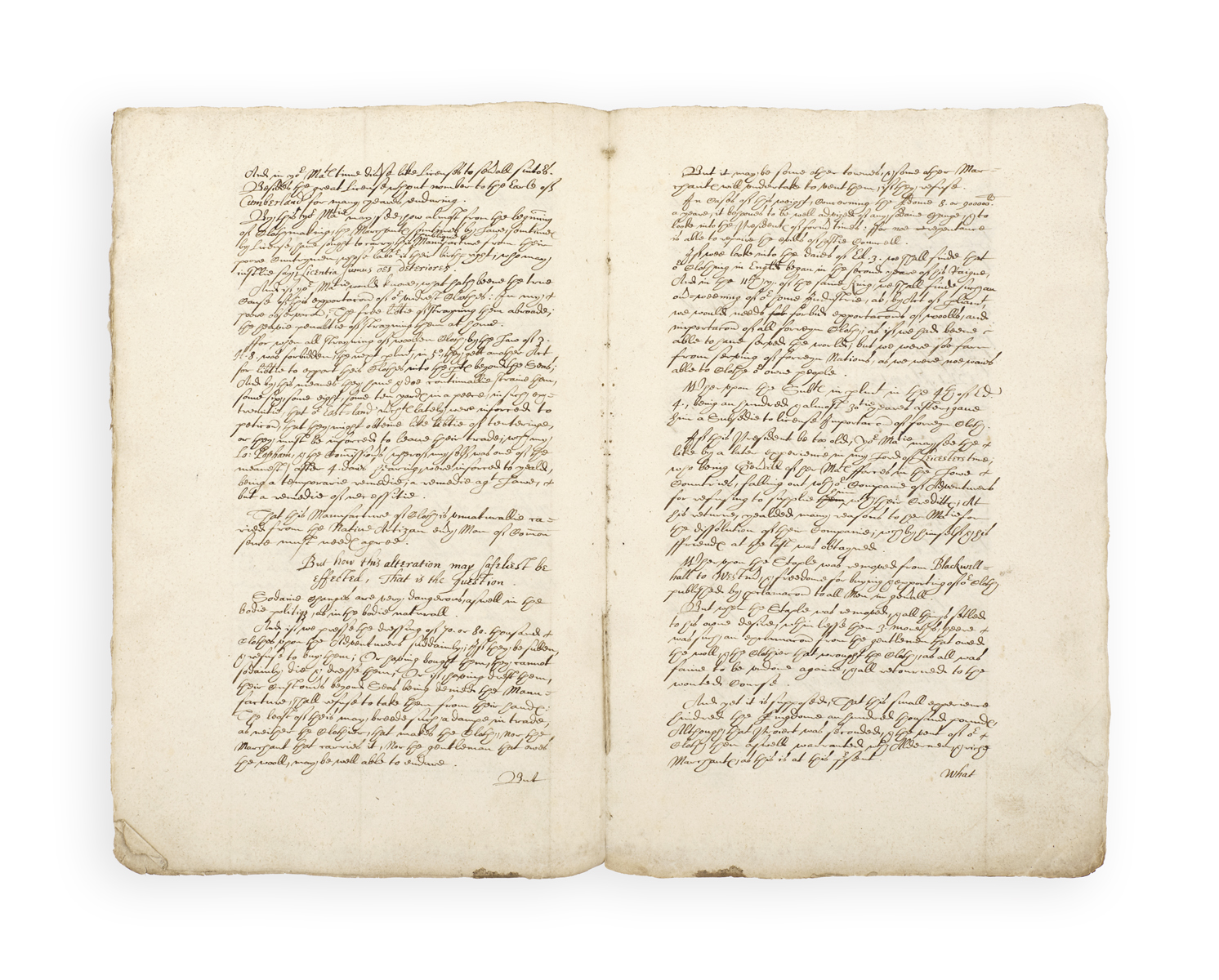

Scribal manuscript on paper, folio, pp. [18]; pillars and grapes watermark, written in dark brown ink mostly in a neat secretary hand, the titles and headings in an italic hand (by the same scribe); conjugate blank to title-page cut away, slightly toned at edges, else in very good condition; evidence of earlier stitching.

Added to your basket:

‘Enchiridion. Certaine breife Remonstrances offered unto his Ma[jes]tie … Touching divers Inconveniences growne into the publique Weale by meanes of The Netherlanders and our owne Company of Merchant Venturers’.

A fine, unpublished manuscript treatise on the balance of trade, dedicated to James I, by the administrator, politician, and collector Sir Walter Cope (c. 1553–1614).

Not born into wealth, Cope was a junior cousin of Mildred Cecil, Lady Burghley, and allied himself to the Cecils as they rose in power, becoming gentleman usher and then secretary to William Cecil, Lord Burghley, and a trusted friend to his son Robert, the Earl of Salisbury. Burghley secured him a post in the Court of Wards in 1574 and eased his passage to Parliament in 1589; a steady accrual of positions and status followed. Knighted by James I in 1603, he was appointed gentleman of the privy chamber in 1607, joint keeper of Hyde Park in 1610, Registrar of Commerce in 1611, and Master of the Court of Wards in 1612, and regularly entertained the King and Queen at his house ‘Cope Castle’ (later Holland House) in Kensington. A committed imperialist with an interest in trade, he served on the Councils of the Virginia Company (1606), the Newfoundland Company (1610), the Northwest Passage Company (1612) and the Somers Islands Company. In 1612–3 he was on several commissions for the augmentation of revenue, cloth exports, and alum works, and it was in this context, as well as James I’s dire need for new sources of revenue, that Cope drafted the present Enchiridion.

‘Every man, with the new yeare, studies to present your Majestie with a new years gifte, some with Skarves, some with gloves, some with Garters, I with a poore glasse [i.e. mirror] of the present time, hoping your Majestie is not of the disposition of our late Queene, who, for many years refused to looke into any, least it might report unto her the wrinkles & stepps of Age.’

Cope’s mirror reveals the ‘wrinkles & decaies of State, encroached upon the lib[er]tie of your Sub[jec]ts by forreyne Pollicies’, lamenting in particular England’s export of raw materials ‘by License or stealth … untanned, unwrought, contrary to Lawe’, to the detriment of our ‘poore Artisans’; and its neglect of fishery and shipping, all of which have allowed the Dutch to reap the lion’s share of profits from manufacturing and global trade. The Netherlanders, ‘having in their hande the very Staple of Moneys and Merchandize of Europe, being strongest by Sea, ritchest by land, & soe neere our Neighbours, may more offend us then any Nation of the world’, and they do so with the complicity of the Merchant Adventurers, whose monopoly on the export of undressed cloth is deleterious to British manufacturing. Similar sentiments apply to the neglected fishing and shipping industries. The Dutch overtake us in the East Indies and Turkey, they employ 4–500 ships to transport British coal ‘whiles our Shippes lie by the walles for want of worke’, and 3–4000 busses (herring boats) and other fishing vessels ‘to take & carry away the fish out of your seas, whereby they relieve Millions of their people, whilst your Coast-townes & greatest Cities, wanting trade, runne to ruyne’.

It was precisely these sorts of fears and arguments that would lead, in 1614, to James I’s dissolution of the Merchant Adventurers, and their replacement with a New Company under the merchant William Cockayne. The ‘Cockayne Project’, which granted the new company a monopoly on dyed and dressed cloth with the aim of promoting those industries locally, was an unmitigated disaster – not only was current manufacturing insufficient to process the raw cloth, but the Dutch refused to buy over-priced and inferior finished cloth, and a trade war ensued that depressed the cloth trade (Britain’s main export) for decades.

Had James listened to Cope instead of Cockayne’s get-rich-quick solution, the situation may have been rather different. Cope recognised that ‘sodaine changes are very dangerous’ and that any changes in trade policy would have to be committed by stealth and incrementally, so as not to shock the market and warn the Dutch of an imminent threat: ‘if we presse the dressing of 70 or 80 thousand Clothes upon the Adventurers suddainly; & if they be sullen and refuse to buy them; Or having bought then, they cannot soadinly die & dresse them; Or if having drest them, their Custom[er]s beyond Seas being denied the Manufacture, Shall refuse to take them from their hands: the least of theis may breede such a dampe in trade, as neither the Clothier, that makes the Cloth, nor the Merchant that carries it, nor the gentleman that owes the wooll, may be well able to endure’. Cope also recognised that Dutch boats that took away the cloth also brought vital commodities, especially to the North, and the Netherlands themselves are viewed not as antagonists but exemplars: ‘behold & imitate the politique & industrious Courses of this wise, provident, & overworking Nation, who, in their times of warr, have raised themselves to that greatnes & virtue as noe people have done since the Romans time’.

Cope’s own solution, offered in a series of ‘Remedies’ devoted to each commodity, was a careful devaluation of the currency, control on the export of bullion, reduced taxation on coloured cloths to promote manufacture, and the promotion of the fishing and shipping industries.

Figures mentioned in passing here include Sir John Popham, whose project to reduce unemployment by encouraging emigration to Virginia was supported by Cope, and the vintner John Keymer, another follower of Cecil and friend of Sir Walter Ralegh, whose own ‘Observations touching trade and commerce with the Hollander’ circulated in manuscript at the time and were later attributed to Ralegh (who had a copy). Though his grasp of personal finances sometimes fell short (he apparently died with £27,000 of debts), Cope was fastidiously incorruptible and admired by John Stow and Robert Cotton. John Tradescant stocked his garden with exotic trees, and he possessed ‘the best-known Wunderkammer in England in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries’; and he was a significant early donor to the Bodleian, giving forty of his 215 medieval manuscripts to the Library in 1602 (see Watson, A. ‘The manuscript collection of Sir Walter Cope’, in Bodleian Library Record, 12 (1987), pp. 262–97).

Given his close contact to James I at the time of its composition, Cope’s Enchiridion, or a version of it, was clearly presented to the King; but evidently it circulated in other manuscript copies like the present, produced by a professional scribe. We have traced three other examples: Trinity College Cambridge MS 698/1, and State Papers 14/71/89 (dated 1612 in another hand) and 90 (a rough draft with corrections, apparently submitted to Ralegh for his consideration).

See Fulton, The Sovereignty of the Sea (1911).